Political division takes hold of Christian communities in Brazil

The outcome of the October election is uncertain. While evangelical candidates concentrate on defending traditional values, some Christian supporters of Lula back his social policy.

SAO PAULO · 16 MAY 2018 · 12:03 CET

The political picture in Brazil is uncertain. The impeachment that expelled ex-President Dilma Rousseff from power in April 2016 has given way to a deep-rooted division within the country: a division between the incumbent Workers’ Party (PT) – the party of ex-President Rousseff and ex-President Lula da Silva – and its critics – who are split between big businesses and landowners, and conservative regions of the population, among which are many protestant communities. And it does not appear that the October elections will resolve the confrontation.

The lack of clarity in Brazil’s political future is compounded by an atmosphere of violence that has grown considerably in recent years and is also related to the country’s land conflict.

According to Le Monde Diplomatique, 61 activists died in the Without Land Movement in 2016, whilst in 2017, the number of deaths increased to 70.

In March, the murder of the Socialism and Freedom Party’s (PSOL) city councillor, Marielle Franco, councillor in the City of Rio de Janeiro, also had a notable impact – a fact that the Brazilian Evangelical Christian Alliance (Aliança Cristã Evangélica Brasileira) has publicly condemned.

Tensions rose during the trial of ex-President Lula da Silva, who was convicted and imprisioned in April for crimes of corruption, as revealed in the Lava Jato Operation (Operation Car Wash) that continues to investigate the laundering of public money by oil company, Petrobras, and construction company, Odebrecht. The disagreements resulting from this process have also taken root among the different Protestant communities in the country.

THE TRAIL AGAINST LULA

At the other end of the spectrum lies journalist Jarbas Aragão, also an evangelical Christians, who argues that Lula “was judged by the courts in two instances, firstly by the Supreme Court of Justice (the Tribunal), and also by the Supreme Court”. He adds that “his alegation is that there is no proof, but nobody who receives corrupt money is going to give a reciept of it”.

For Aragão, “it is very clear that the majority of Brazilians believe that Lula and the Workers’ Party are guilty”. However, the rejection of the ex-President is not exclusively linked to the accusation of corruption. “The Workers’ Party has invested in a form of cultural marxism in universities and large parts of the press, presenting abortion and gay marriage as good ideas”, suggests Aragão.

“The majority of evangelicals have a moral standard,” laments Ramos, “and they have come to consider neoliberal capitalism as part of their confession of faith”, he adds with respect to the alternative policies that have been presented.

EVANGELICAL AGENDAS IN BRAZIL

Where Aragão and Ramos do coincide is in recognising the social policy implemented by the Workers’ Party throughout Lula’s two presidential terms and Dilma’s term and a half. “I admit there was a period when the economy was doing well and that they did good things for the poorest people”, the journalist comments, “but over time we saw a lot of long-term damage”.

For his part, pastor Ramos remarks that “during the three terms that the Workers’ Party led the federal government, it carried Brazil into extraordinary economic growth and erradicated hunger by promoting a socio-economic movement that brought 40 million people out of poverty”. Although, he also recognises that “they stopped making basic reforms in areas such as tax, agriculture, urban reform, policy, and the management of the media”.

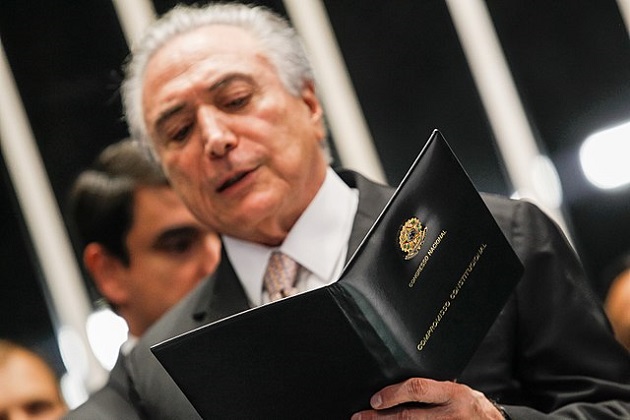

Opinions once again diverge over the present situation. After the dismissal of Rousseff, the then-Vice President Michel Temer took power. Temer, from the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), is also accused of passive corruption and his popularity has plummeted since 2016 to reach just 4% in April of this year, according to the Association of Political Communication.

Arivaldo Ramos accuses Temer of being “behind the coup d’état against Dilma” and reiterates that “he has no popular support because he has followed his neoliberal pattern and increased social inequality in the country with the annulment of workers’ rights”, he says in reference to the Labour Reform that Temer’s government approved in 2017.

On the other hand, for Aragão, “he has made important changes to the economy and the country is somewhat better”, although he states that “he is far from being good president”.

“THE EVANGELICAL VOTE IS GOING TO BE SPLIT”

The energy of this debate now focuses on the run-up to the first round of presidental elections that take place on 7th October, and the second round on the 28th October. Everyone agrees that Brazil is governable; what they don’t agree on are the candidates, who, according to the Aliança, “are now offering themselves, some crawling out of their graves, others drawing attention in a more radical way, and still others concealing their true political commitments and ideological identities”.

For the pastor and coordinator of the Brazilian Evanglical Front for the Rule of Law, Arivaldo Ramos, “the only one who can execute leadership with the necessary recognition is Lula da Silva,” who continues to express his intention to present himself as candidate for the Workers’ Party despite the fact that legislation prevents it. Ramos predicts: “I think that if Lula is prohibited from participating in the elections, the person he chooses will have great possibilities of assuming the leadership of the nation”.

Aragão concentrates on the pre-candidates (the election campaign has still not begun) named as Christians, although he doesn’t see a clear victory for any of them. He refers to the ecologist and ex-Minister of the Environment under Lula, and member of Assemblies of God, Marina Silva, who presented her candidacy for the presidency in 2010 and 2014 without getting to the second round; Cabo Daciolo, who was expelled from the PSOL and has now become a pre-candidate for the party Patriota; and the Catholic and ex-military officer of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) Jai Messias Bolsonaro.

“There are some candidates that try to close in on the religious world, among them candidates who consider themselves evangelicals”, notes pastor Arivaldo Ramos, who believes that “the evangelical vote is going to be split because any one of those candidates has the possibility of winning over those sectors”.

RELATIONSHIPS IN AN DIVISIVE CONTEXT

The crisis of ideological coexistence in the country is also a reality within churches. Spiritual convictions play an important role in the electoral agenda and in the National Congress, where the Evangelical Caucus has tried to homogenise Protestant representation without the consent of all communities.

“Division among evangelicals caused by the coup d’état against Dilma is not going to be easily overcome because, more than establishing a rupture in the political picture, it has revealed an ideological division within the evangelical camp,” says Ramos. “I believe that in the medium term, we will begin to live better with each other despite our differences, but that for a time, it will generate a surge of new evangelical communities with clearer cut ideological differences that won’t be treated as crises of faith.”

On the other hand, the journalist and communicator for the Aliança Bíblica Universitária de Brasil (ABUB, which comes under the IFES movement), Jessica Grant, insists in a blog post on the power of relationships between Christians: “It seems very important for us to correctly position ourselves and fight for what we believe in, but I think that the way in which we fight speaks even more deeply of our actions, and that our relationships could be the key to seeing transformation”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - world - Political division takes hold of Christian communities in Brazil