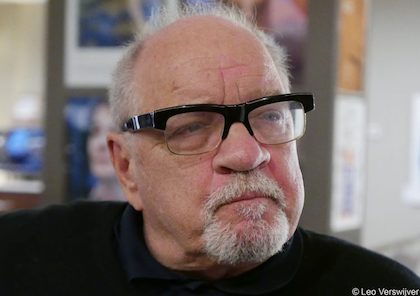

Schrader’s tormented faith

For Paul Schrader’s characters, salvation is often synonymous with self-redemption. Atonement for guilt is sought through violence, which, far from being divine, is profoundly human.

13 NOVEMBER 2018 · 14:01 CET

Stories about pastors in a crisis are not to everyone’s liking, but they are as real as life itself. This is what the last film by Paul Schrader – starring Ethan Hawke –, First Reformed is about.

The name is significant because it refers to a historical church in crisis. In church sociology, such churches are called “residual churches”: on paper they have hundreds of members, but barely a handful of people actually turn up at their meetings. Toller is a minister who is full of doubts, battling with guilt and illness, with clear echoes of Winter Light. It is a dark and tormented film, a far cry from the values genre.

The film has, in fact, been presented at the congregation that he attends with his wife, who comes from the same background as him. The Presbyterian church of Mt Kisco is close to where he lives in the State of New York. The pastor Dale Southhorn has even provided advice on the film, which has been shown at evangelical seminaries such as Fuller, where Schrader himself gave a talk. The film has been recommended on Christian websites, which however warn readers that it is not an easy watch, despite its surprising ending.

CALVINIST EDUCATION

Schrader was brought up in a strict Protestant family living to the east of Lake Michigan, where Dutch surnames are common and Calvinist heritage is strong. In his church, going to the cinema was frowned upon and, as a result, Paul watched his first film at the age of 17. It was Disney’s The absent-minded professor, which in the early 60s was being shown at a cinema in the nearest town centre. He remembers the experience being very disappointing.

In an interview given to Film Comment, he revealed that when he was little, he wanted to be a church minister. At home they were always talking about theology, like the family in his film Hardcore (1979), where the brother and father of the character played by George Scott discuss unforgivable sin. It’s Christmas and the family are gathered together. They sing hymns and a reverent prayer is said at the table. At church, the pastor explains the first question of Heidelberg’s catechism:

“What is your only comfort in life and death? That I am not my own, but belong with body and soul, both in life and in death, to my faithful Saviour Jesus Christ. He has fully paid for all my sins with his precious blood, and has set me free from all the power of the devil. He also preserves me in such a way that without the will of my heavenly Father not a hair can fall from my head; indeed, all things must work together for my salvation”.

TWO SEMINAR STUDENTS

Both Schrader and his future colleague, Scorsese, studied theology. The only difference was that the Italo-American director was a Catholic and went to a seminary in New York – next to the Upper West Side cathedral –, while Paul studied at the Protestant seminary of Calvin College, in Grand Rapids. Together they would revolutionise the cinema of the 1970s with films full of guilt and loaded with violence.

Paul’s father had German origins, but he entered the Dutch reformed community when he married a woman of Friesian origins. They were farmers, although his father owned a factory, similar to the main character in Hardcore. In 1948, Schrader was born into a family where life revolved around the church. In his book of interviews, Schrader on Schrader and other writings, he says that throughout his secondary education, he didn’t really come into contact with people outside the church.

At home, the Bible was read consecutively every day. He explained that one of the reasons that he wanted to be a missionary was that his name came from his mother’s favourite Bible characters, Paul and Joseph. In the long and boring church services that he had to sit through, he would read the bits of the Bible that mentioned them, finding them fascinating. Having rejected hyper-Calvinism in the 1920s, the Christian Reformed Church was a pretty evangelical denomination, balancing its emphasis on God’s sovereignty with the free offer of the Gospel. In a recent interview, he admitted that he left the church behind, but not the need to proselytize.

TORMENTED STRUGGLE

In the book Schrader on Schrader and other writings, Paul recounts the time when someone said to him, “don’t do this”, and he immediately though, “Well, why not? What would happen if I did? Would it be interesting?”

Above all, Schrader was rebelling. He turned his university newspaper into a subversive publication and was expelled from it, as well as from all the jobs he held, with the exception of his job at the factory owned by his father – whom he tried to understand in Hardcore. He followed his brother Leonard to California, where he studied cinema and submitted a thesis in 1972 entitled “Transcendental style in film: Ozu, Bresson and Dreyer”. With the support of the film critic Pauline Kael, he worked for the American Film Institute and, together with his brother, wrote the script for Sydney Pollack and Robert Michum’s film Yakuza. The magazine Film Comment has published the correspondence between the two brothers, when the late Leonard went to Japan as a missionary, after having left the church like Paul.

In 1973 Paul had nothing. He had broken up with his wife and with the girl he had left her for. He didn’t have a job and was living in a car. He was plagued by suicidal thoughts and was drinking a lot to take the edge of strong pains that turned out to come from an ulcer. His obsession with violence and pornography show us that he not only saw himself as the character that he wrote for Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver, but also as the daughter whom the father in Hardcore is looking for after she goes to a Calvinist youth convention and disappears, ending up in the porn industry.

FEELING OF SIN

As the late Chicago critic Robert Ebert observed, "One thing [his] movies have in common is a very strong, visible sense of sin”. Even his most recent work with Lindsay Lohan and the porn star James Deen, The Canyons, is a distressing vision of the moral emptiness of humanity. Schrader has said that anyone who has had a deeply Christian upbringing will be interested in guilt, redemption and the metaphors for salvation.

"What kind of church do you belong to?” Niki, the prostitute in Hardcore, asks the father. "It's a Dutch Calvinist denomination… They believe in the 'TULIP.'”, George Scott answers. The character explains to her that “It's an anagram. It comes from the Canons of Dort. Every letter stands for a different belief”. At her insistence, he spells out the five theses of Calvinism, beginning with the first: "T stands for Total depravity, that is, all men, through original sin, are totally evil and incapable of good”. For this reason, he confesses with Isaiah (64:6): “All of us have become like one who is unclean, and all our righteous acts are like filthy rags”.

A similar dialogue at the airport of Las Vegas, shows us the extent to which Schrader’s work is difficult to understand without his Christian upbringing. The surprising thing is that this prostitute, who claims to be “Venusian”, is much nobler in her affection and generosity than this apparently irreproachable Christian. The hypocrisy and falseness of certain puritan morality is highlighted here, alongside the inhumanity of this sordid world, couched in neon lights and descending into hell. This is why many have described this film as reactionary.

A SEARCHER

This film, like all Schrader’s films, is part of the obsession of the new Hollywood of the 1970s for the John Ford classic, The Searchers. It is considered to be one of the best Westerns in the history of cinema, based on a novel by an author of short western stories, Alan Le May. He took his inspiration from the real-life story of Cynthia Ann Parker, who at the age of 9 (around 1836) was taken by the Comanches, after they massacred her family.

This story not only inspired Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Schrader’s Hardcore, but also the first Star Wars, Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg’s Jaws, and Coppola’s The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. John Wayne’s consuming search shows us a solitary man, condemned to wander for all eternity. It is a sombre and melancholic story of epic dimensions, which shows us the Fordian hero, on the one hand hard and noble, but also neurotic and racist.

When Schrader filmed the first scenes of Hardcore, it still had the provisional name of Pilgrim. As in most great narratives, it tells the story of a journey, which we are meant to relate to life itself. In relation to Taxi Driver, Schrader describes this when he says: "Travis's is not a societally imposed loneliness or rage, it's an existential kind of rage". He was then reading Sartre’s Nausea, which explains the harshness of his films. Hardcore originally didn’t have its current happy ending, but closed with an absurd accident.

AFFLICTED VISION

For many, Schrader’s best film is Affliction (1997), for which James Coburn won an Oscar for best supporting actor. He said that the film had something of the style of Bergman, the Swedish director and son of a Lutheran pastor. It seems to be inspired by Winter Light (1962). Snow covers both films and they both tell stories of a cruel coldness, in which the silence of God highlights the tragedy of a desperate humanity.

The main character in Bergman’s film is a pastor who has lost his faith and is incapable of committing himself to the women he loves, while Schrader tells the story of a divorced policeman who scares away his partner, despite his dreams of rebuilding a life with her and obtaining custody over his daughter. Both characters live a life of anxiety under the weight of guilt, surrounded by violence and bereft of all hope.

In many of his films, the notion of grace is reflected in the love of a woman. In American Gigolo (1979), she is the one who sacrifices her social position for someone who is unable to express love. In Light Sleeper (1992), it is again a woman who offers a maternal refuge to the drug dealer. As in Bergman’s film, these people aren’t believers. Redemption is found outside the church.

IS REDEMPTION POSSIBLE?

Another of his scripts for Scorsese was Raging Bull (1980), which tells of the self-destruction of a boxer. The film closes with a final quote from the blind man healed by Jesus, who knows that all he knows is that now he can see. This is not, however, according to Schrader “salvation by grace”, since he says that Scorsese was the one who included the words from the gospel of John at the end of the film. The decision seems to have been the result of Scorsese’s near-death experience due to a drug overdose. In hospital, he pleaded with God to save him and he miraculously survived. "[It] always just seemed wrong to me”, Schrader says. “Jake is the same at the end as he is at the beginning. He hasn't learned anything".

His strangest collaboration is, without a doubt, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), based on the novel by the Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis, which got him kicked out of the Orthodox Church in 1955. Schrader sees in this film a clear progression from the Greek Orthodox Church, to Roman Catholicism, passing by Dutch Calvinism. This vision of Christian theology is one of the most interesting elements of the film, but the end of the film shows the triumph of some sort of Nietzschean superhero.

For the scriptwriter, The Last Temptation of Christ is not a religious or transcendental film, but rather a psychological film, about the internal torment of spiritual life. And that is what the book is about, making it a very faithful script – rather than faithful to the Gospel – except in the scene where Jesus tears out his own heart, which was Schrader’s idea. This is a reminder of the image of Calvin, heart in hand, which appears on the emblem of Schrader’s university. But who is God for him?

Schrader is constantly trying to find out how to obtain redemption. His upbringing in Protestant orthodoxy taught him that blood has to be spilt for the redemption of sin, whether it be our blood or the blood of Jesus Christ. The problem is that for his tormented characters, salvation often becomes a sort of self-redemption. Redemption from sin is sought through violence which, far from being divine, is deeply human. In Affliction, this aggression is the result of original sin, clearly manifested in three different generations.

IRRESISTIBLE GRACE

Schrader’s films show us the “total depravation of man”, but where is that “irresistible grace” proclaimed by Calvin? We all know that terrible feeling of despair produced by sin. We know that the strength to defeat it is not found within ourselves. When we analyse our lives, we realise that there is something twisted. We not only do what we shouldn’t, but like the boxer in Raging Bull, we do not see or understand what life means.

When people talk about grace, they tend to quote the poem by Francis Thomson, The Hound of Heaven. What many people do not know is that he was a Catholic, not a Protestant. Thomson was born into a family of English converts to Roman Catholicism in the nineteenth century. They even sent him to a seminary to train to be a priest, but he left, lacking vocation. His father then tried to persuade him to become a doctor, but he didn’t get through his studies, becoming an opium addict following a confrontation with him. In his despair, Thomson began to consider committing suicide but he was dissuaded from this course of action by a vision. Shortly afterwards, he met a prostitute, who gave him lodgings and, in some way, saved his life. In his poem, he sees in her the grace of God pursuing him.

According to US pastor, John Piper, faith is to trust, rest in and be satisfied in what God is to us in Jesus Christ. His salvation is not only a gospel of grace, but the Gospel itself is the God of Grace, whose action cannot be explained other than through the fact that his throne is upheld throughout eternity by the reality of his grace. The reality of his justice will always be stronger than our condemnation. As C.S. Lewis says, there is no better expression of the sovereign will of man than hell.

The only thing that can save us from the hidden world within us is the triumph of the grace of God in Jesus Christ. That is how love wins.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Schrader’s tormented faith