The Joker’s mask

Todd Philipps' film is an adult exploration of the anatomy of evil, closer to a Kafkaesque tragedy or to Dostoyevsky’s novels than to the children’s universe of comic book superheroes.

30 DECEMBER 2019 · 10:43 CET

The Greeks were right. People need masks to say the truth. Films are all mirrors, even if we do not like what we see in them. One of the biggest surprises this year – together with “The Irishman” by Martin Scorsese – is “Joker” by Todd Philipps.

Although it has a definite 70s feel, it reflects our present reality. It shows the blood and tears that fall behind the masks that cover our faces.

Ever since humans learnt how to tell stories, we are happier to accept fiction than reality. It is part of a game, it amuses and entertains us. We all know that the events aren’t true, that it didn’t happen as they say it did, but we don’t care. As with white lies and half-truths, we believe that they don’t hurt anyone and that they even protect us…

Batman was born in 1939 with the lie that Bob Kane (1915–98) was the only creator of the Dark Knight, while the co-author, Bill Finger (1914–74), lived and died without receiving any recognition. All the comic books are signed Kane, and in all the TV series and products this same name appears as if etched into stone.

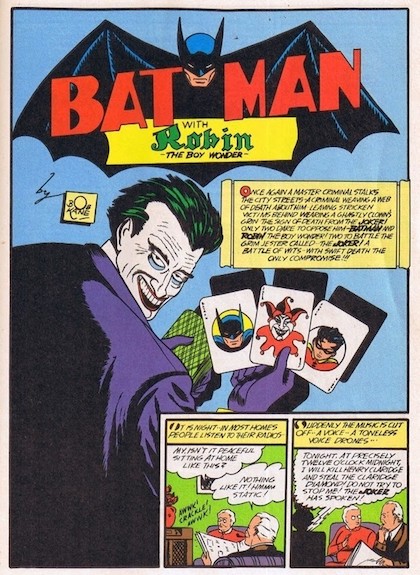

It was as the creator of Batman that Bob Kane introduced himself to a 17-year old, at a tourist centre in the Pocono mountains of Pennsylvania. Jerry Robinson (1922–2011) had arrived a few days earlier hoping to study journalism at Syracuse University. Instead Kane offered him a job in New York, where he created the Joker while he was living with his aunt in the Bronx, studying in Columbia, and inking in Batman drawings by night.

FOR EVERY HERO THERE IS A VILLAIN

In New York, Robinson lived close to Kane’s parents. He would meet up with Kane and Finger in the park that is still home to Edgar Allan Poe’s house in the Bronx. Bill wrote the stories, Bob sketched the drawings and Jerry finished them off, inking them in and doing the lettering. Together, they visited the Museum of Modern Art and the Met on 5th Avenue, getting ever deeper into Batman’s world. The name of Gotham had already been used by Washington Irving to refer to New York in a satirical book written in 1807.

Batman was born into the pages of the Detective Comics (DC) series. Sherlock Holmes was one of the authors’ first references, with Robin providing a peculiar kind of Watson. But as with all heroes, there was a villain. Joker is to Batman what Moriarty is to Sherlock Holmes. Robinson came up with him when thinking back to the games that he used to play with his family, often using cards. He and his brothers even went to competitions.

When a story’s hero is as dark and tragic as Batman, the villain must be as colourful and smiley as the Joker. He steps out of the card with that clown’s face that watches you intently. When you get the card, he looks back at you with his white face, red lips and green hair. Even in the first story written by Finger, he doesn’t seem to come from anywhere. It is in a story about a murder behind closed doors, where his white face, scraped back hair and permanent smile first come to us. He is inspired both by the joker card and by the image of Conrad Veidt in the film “The man who laughs” (1928), based on a text by Victor Hugo.

70s NOSTALGIA?

Although the story is set in 1981 – we don’t get a date, but that is the year of the films playing in the cinemas, such as “Blow Out” by Brian de Palma, “The Gay Blade” Zorro film, and “Excalibur” by Boorman – it has a 70s vibe, given that the beginning of decades often still hangs on to the fashions and styles of the last one. Some 80 years ago it looked like the Joker was going to die, stabbed by accident in a fight with Batman, but the editors added an ambulance to remove the Joker’s body, and the last drawing shows the nurse saying “he will live”.

Those who know the comic book story will get the references in Todd Phillips’ film straight away, even in the name of Fleck – DC banned the use of the word “flick”, because when capitalized it could be mistaken with a certain four-letter word, still taboo for the US’ conservative society. Most people will think that they are watching a film from the 1970s – so much so that it could pass off as a rereading of Taxi Driver for “millennials”. When the Warner logo designed by Saul Bass appears, you might be about to see Serpico or Network, but there is no doubt that the reference for Joaquin Phoenix is that of Travis played by Robert De Niro.

In American cinema, the return to the 70s points to New Hollywood’s exploration of reality. The cameras go into the streets even on television. The studios risk showing the dirty piles of rubbish in Times Square, violence on the streets, and the porn cinemas. Joker is not a film about nostalgia for a dirty New York, but a return to the real time of a cinema that has suffocated itself in special effects and dazzling fast-paced action. When I went to see Joker with the technician I work with on the radio, Dani Panduro, I wondered whether I had gone back to being that same adolescent that was fascinated by “The Last Picture Show”. It isn’t that I have stopped being who I was then, but a certain mask broke, letting through the blood and tears of a darker inner self.

AN ANATOMY OF EVIL

A moral criticism of the film would express horror at the empathy that it creates towards the villain’s mind. More than just acting, Phoenix serves up a veritable performance: the great “special effect” of a quasi-method actor, capable of losing 23 kilos in 15 days in order to embody his character.

The story is far removed from a superhero tale. It is more reminiscent of the stories of nocturnal vigilantes by Charles Bronson, in scenes like the vengeance of the girl humiliated in the subway by a group of drunk white guys. Joker isn’t a terrorist like the Tom Hardy of the Dark Knight, nor an anti-system activist, as in V for Vendetta or Mr Robot. Involuntarily, he becomes a symbol for the social malaise through an explosion of individual anger, which causes unpredictable chaos, without well knowing what he is doing.

Nothing in Todd Phillips’s career would have suggested that he had something like this up his sleeve. It is a surprising film with an impeccable production that closely follows the character’s inner labyrinth. It was awarded the Venice golden lion and it was given a ten-minute standing ovation in Toronto. I wouldn’t be surprised if Phoenix was given the Oscar, even though the film is far from being everyone’s cup of tea.

Its darkness makes it distressing to watch, and this feeling is highlighted by the music played by the Islandic cellist Hildur Guônadottir. It is an adult exploration of the anatomy of evil, closer to a Kafkaesque tragedy or to Dostoyevsky’s novels than to the children’s universe of comic book superheroes.

What makes this story so compelling is not only the interplay between what happens in the Joker’s head and what is happening in reality, which is left ambiguous, but also the pathetic nature of the loneliness of this unfortunate character. His absurd idea of trying to make it as a comedian not only pays tribute to Scorsese’s “King of Comedy” with the best supporting actor role that De Niro has played in a long time, but it also provides a brutal contrast with the character’s pain and the imposture expressed so well in the song taken from Chaplin’s “Modern Times”: “Smile, though your heart is aching”. The epiphany that the Joker has when he sees the film reflects the false pretence that social media lives off, that everything is always marvellous. Above all, never stop smiling. It is truly pathetic.

IN SEARCH OF THE FATHER

There is a clear social reading of this film. As Phillips himself admitted, “the movie is about this loss of empathy that I think has been amplified in the last few years for many reasons, in culture and yes, our current administration but also the Internet”. The Director believes that “when you have a world like that, you get the president you deserve and to me when you have a world like [Gotham] you get the villain you deserve”. So “while the movie takes place in the late-70's, early-80's we wrote it in 2016 and 2017 and so, of course, there's a little bit of a mirror to what's going on in our times”.

As in all major stories, Joker is also the story of the search for the Father. The character is some sort of Norman Bates, with a mother like the one in Psychosis. Shut up in her house, he lives in a sort of unhealthy dependence on her, while he hides a dark family secret. This gives him a psychological dimension that explains not only his wounds, but also the rage that he hides in the Joker. Those who do not understand the character’s violence have not been able to identify themselves with that experience. What’s more, they are forgetting about the darkness in their own hearts (Jeremiah 17:9).

Phillips says that “it is a film about identity and about childhood traumas”. The character wears a mask throughout the first part of the film, but it is when he dares to remove it that he comes alive. It is only when he wears the Joker’s make up though that he discovers who he really is. We reach the truth about his character through his mask. As with the ancient Greeks, the “persona” comes from theatre. Because, who is the Joker? The problem, according to Phillips, is that he is a bad person who discovers the evil within him. He tells the therapist, “All I have are negative thoughts”.

“If chance be the father of all flesh, Disaster is his rainbow in the sky” – says the poem that Steve Turner wrote in New York. The news with which the film starts would be “the sound of man worshipping his maker”.

But if the author of life is the Father of Jesus Christ, there is hope for the chaos that reigns on our planet. And this is a God who reconciles us through his suffering, to show us the love of the Father for his children. It is that love that the world did not know (1 John 3:1), but that we can know through the work of the Spirit. Through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, we know his great mercy, which allows us to be reborn for living hope (1 Peter 1:3). We are no longer what we seem to have been, but are what we will one day be, thanks to Jesus Christ.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The Joker’s mask