Lost significance

In some of Europe’s most secular countries like France, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands, Ascension Day is a public holiday.

22 MAY 2023 · 09:30 CET

Ascension Day is a largely forgotten celebration.

Surprisingly, in some of Europe’s most secular countries like France, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands, it is a public holiday.

Equally surprising is that in the United Kingdom, where the central role of the Anglican Church was evident in Charles’ recent coronation, it is not a holiday, despite being celebrated by the Anglican communion worldwide.

Few Europeans know what was being celebrated last Thursday. Few European Christians would have even given it a thought. While Christmas and Easter are widely observed and understood, the significance of Ascension Day is lost on the public, Christian or otherwise.

For those who have thought about the topic, it’s – well – a little embarrassing. The idea of Jesus ‘lifting off’ or levitating to some higher place, maybe a few kilometres above the highest flight paths, boggles the modern mind. Frankly, it’s ‘foolishness to the Greeks’, as Paul would have put it.

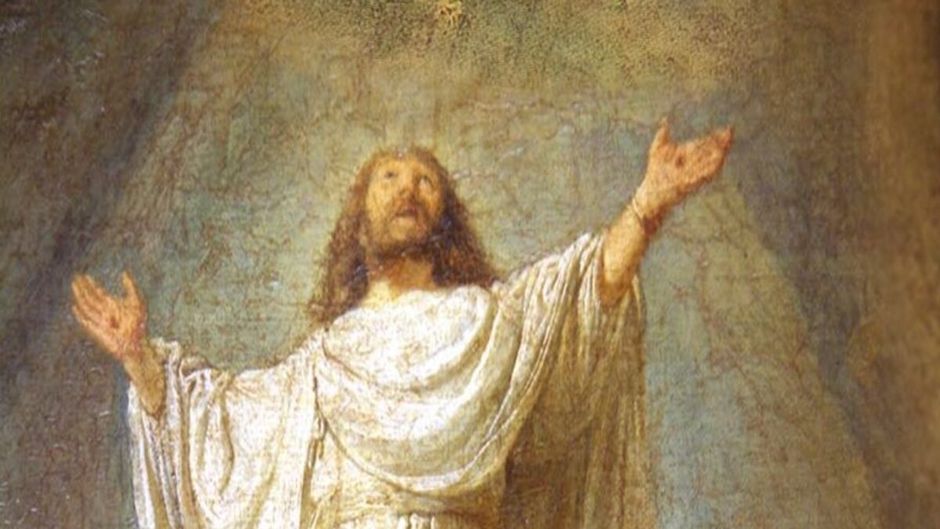

Yet the ascension of Christ (painted above by Rembrandt) has been a Christian tradition since the early church. The Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed both affirm that Jesus rose from the dead on the third day, and ascended to heaven, where he is seated at the right hand of the Father.

Ascension Day is an intrinsic link in the unfolding events of the death and resurrection of Jesus, followed fifty days later by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

For ten days before Pentecost, Christ, in his resurrected-yet-physical body, is translated into another realm. His ascension was a prerequisite for the Spirit to be poured out. Absent in body, he would be near in spirit. But where did he go to?

Ticket to heaven?

Last Thursday, we marked 50 years of YWAM The Netherlands with a celebration at the Heidebeek training centre, attended by some 2000 present and past students, staff and friends.

For the past 40 years or so, we have held an Open Day at Heidebeek on Ascension Day. For that was the day Jesus told his disciples go into all the world and make disciples among all peoples.

Heidebeek, a ‘springboard for world missions’, along with other YWAM centres across Europe, has equipped and sent literally thousands of young people to do just that, in all sorts of ways.

Yet I suspect that sometimes the message we have offered was of a ‘ticket to heaven’ when we die. But is this really the Christian hope?

Theologian Tom Wright, in his book Surprised by hope (2008), challenges the misunderstanding ‘that has … misled people into supposing that Christians are meant to devalue this present world and our present bodies and regard them as shabby or shameful…’

‘Heaven, in the Bible, is not a future destiny’, he argues, ‘but the other, hidden, dimension of our ordinary life—God’s dimension, if you like. God made heaven and earth; at the last he will remake both and join them together forever’.

Questions about heaven

During our celebrations on Thursday, news came that a very close friend had passed away. The next day the news spread around the world that Tim Keller had also succumbed to his battle with cancer.

When we are confronted with death, questions about heaven, final destinations and life-after-death flood our minds. Wright’s message in his book is that too often we have missed the teaching of the Bible on the Christian hope. He poses two inextricably linked questions.

“First, what is the ultimate Christian hope? Second, what hope is there for change, rescue, transformation, new possibilities within the world in the present? As long as we see Christian hope in terms of ‘going to heaven’, of a salvation that is essentially away from this world, the two questions are bound to appear unrelated”.

Yet God does not intend to let death have its way with us. When Jesus spoke of the ‘kingdom of heaven’, Wright clarifies, he was really speaking of the ‘kingdom of God’ that had come to earth and not about some postmortem place to which the righteous will be escorted as they breathe their last. No one will be raptured away from the earth to some celestial sphere, he insists. Rather, heaven will be here, on earth, on this very planet.

“The main truth is that he will come back to us”. The Greek word parousia, usually translated as ‘return’ (meaning Jesus’ Second Coming) really means ‘presence’— as opposed to absence. “When a king or emperor visits a colony or province, the word for such a visit is royal presence: in Greek, parousia.”

Wright argues that Paul and the early church held that the Jesus they worshipped was near in spirit but absent in body; but that one day he would be present in body. Then the whole world, themselves included, would know the sudden transforming power of that presence.

Jeff Fountain, Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies. This article was first published on the author's blog, Weekly Word.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Window on Europe - Lost significance