Gender: where next?

Personal journeys, radical agendas and perplexing dilemmas.

24 FEBRUARY 2017 · 11:04 CET

Haven’t you read,’ [Jesus] replied, ‘that at the beginning the Creator “made them male and female,”…?’ Matthew 19:4

‘…the transgender revolution represents one of the most difficult pastoral challenges this generation of Christians will face.’ Dr R. Albert Mohler[1]

Summary

The issue of ‘gender identity’ has risen to prominence with remarkable speed in recent years and demands our attention. This paper begins with a brief survey of different understandings of gender, before examining, distinguishing and contrasting the medical condition gender dysphoria and aspects of transgender ideology. This sets the scene for biblical reflections on the body, sex and gender in the light of the searching questions posed by the transgender phenomenon. The paper concludes with reflections on two challenges which Christians face in a new and changing context of gender confusion.

Introduction

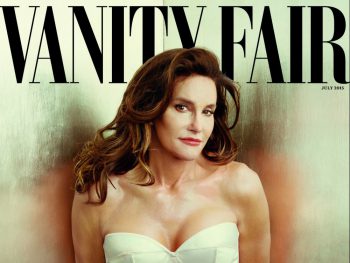

In July 2015, Bruce Jenner’s journey from Olympic icon to transgender woman was announced to the world on the front cover of Vanity Fair magazine with the headline ‘Call me Caitlyn’. In 1976 Jenner had won the decathlon gold medal at the Montreal Olympics and was an all-American hero; in 2015 Jenner won Glamour magazine’s Woman of the Year Award and the Arthur Ashe Courage Award. The journey had not been straightforward: Jenner had experienced gender dysphoria for decades, turbulent family relationships, and a transition that involved taking hormones, hair removal, breast augmentation, a tracheal shave, and facial-feminization surgery.[2]

In the trailer to the reality TV show ‘I am Cait’, Jenner looks forward to the day when people like Jenner will be normal and just blend into society; when a conversation partner says ‘you are normal’, Jenner replies: ‘Put it this way, I am the “new normal”.’ Gender identity issues have become more widespread, more prominent, and more pressing in recent times, and neither society nor church can avoid responding to them.

Understandings of gender

Sex as a biological concept is relatively straightforward: our sex reflects the different roles of men and women in sexual reproduction. Men and women have different genetic endowment (XY and XX chromosomes) and primary sexual characteristics (the parts of our anatomy directly involved in sexual reproduction) and, usually, sex hormones produce different secondary sexual characteristics (such as body hair distribution). However, in rare cases, disorders of sexual development (DSDs) may result in an ‘intersex condition’ in which a person has a non-standard chromosome combination and/or physical sexual characteristics which are incomplete, inconsistent or ambiguous. Intersex conditions do not constitute a ‘third sex’ but variations from the two sexes – male and female – involved in human sexual reproduction. Biological sex ‘is, for almost all human beings, clear, binary, and stable, reflecting an underlying biological reality’.[3]

‘Gender’ was, historically, a grammatical term to classify nouns as feminine, neuter or masculine. The use of the word ‘gender’ in connection with sex, personal identity and social roles is a twentieth-century phenomenon. At one level, the word ‘gender’ often functions as a synonym for the word ‘sex’ (because the latter term has been co-opted as an abbreviation for ‘sexual intercourse’). However, in gender theory, the concept of ‘gender’ is differentiated from ‘sex’ and addresses social, cultural and personal issues such as gender roles, expectations, expression and identity. The result is a concept which is multivalent, complex, multi-faceted, and culturally contested.

On one view, gender differences reflect the outworking of an essential difference between men and women who have inherent attributes, rooted in neurobiological differences, which contribute, alongside cultural influences, to distinct patterns of thinking and behaviour beyond the realms of sexual reproduction. For Simon Baron-Cohen, the ‘female’ brain is an ‘empathizer’ and the ‘male’ brain is a ‘systemizer’.[4] Certain characteristics are distributed among men and women respectively in a way that can be represented by two overlapping bell curves.

For many, however, gender is merely a social construct, established through the apparatus of social expectations. As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex: ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.’[5] That is, differences in opportunity, aspiration, and modes of social interaction which women experience are learned from, or imposed, by family, peers and culture. For feminists, gender norms are problematic because women are socialised into subordinate roles.

For Judith Butler – critic of feminism and leading exponent of queer theory – gender is a performativeaccomplishment, a ‘constructed identity’, established through a ‘stylized repetition of acts’, through which gender is given the illusion of substance. An individual is always ‘doing’ gender, either performing in accordance with socially accepted gender stereotypes (creating the appearance of an essential binary) or deviating from them (in subversive acts which challenge, and dismantle, heteronormative practices).[6] Furthermore, ‘gender cannot be understood as a role which either expresses or disguises an interior “self”.’[7] Here she echoes Foucault, and before him Nietzsche, who argued that our task is self-creation. For Foucault, ‘…there was nothing within or without to which one had to be true – self-creation had no such limits. It was about aesthetics, not morals; one’s only concern should be to fashion a self that was a “work of art”.’[8]

We might well wonder, after this brief survey, whether gender is something a person is, or learns, or does, or feels, or chooses. However, if gender is merely a social construct, performative accomplishment or psychological identity, gender has no necessary connection with our physical sex. Gender identity need no longer be binary but can spring from the unique combination of characteristics, actions, preferences and perceptions each individual possesses. If gender identity is constructed, it may be fluid and plastic; if gender norms are socially constructed, they can be deconstructed.

Gender dysphoria

According to an NHS Choices document: ‘Gender dysphoria is a condition where a person experiences discomfort or distress because there’s a mismatch between their biological sex and gender identity.’[10] Gender dysphoria, if sufficiently intense, justifies a medical diagnosis. Until recently, known as ‘gender identity disorder’, the newer terminology reflects a reluctance to see, or treat, the condition as a problem of the mind and a focus on the removal of distress. The condition is rare: surveys suggest prevalence lower than 1 in 7,000 for men (or 0.014%) and lower than 1 in 20,000 (or 0.005%) for women.[11] More people self-report as transgender (between 0.35% and 0.52% of the population)[12] or identify as gender variant in some way (about 1% of the population).[13]

Gender dysphoria may be transient (most prepubescent children with gender dysphoria simply grow out of those feelings)[14] or persistent; it may be early onset or emerge with new intensity in middle age; it may have no connection, or may have submerged connections, with sexual orientation/attraction.[15] People respond in different ways: some make no alteration to their outward gender expression; some engage in cross-dressing whether in private or in public; some seek medical help and may receive psychosocial treatment (to help them embrace the gender corresponding to their sex) or may be offered cross-sex hormones followed, in some cases, with one or more surgical procedures.

The causes of gender dysphoria remain uncertain and controversial. Neurobiological theories (which consider brain development) and psychosocial theories (which look at the impact of development factors such as distant fathers, parental wishes for a child of the other sex, and emotional or sexual abuse) compete but the research in support of these theories remains limited and inconclusive.[16] Yarhouse concludes that the ‘experience of true gender dysphoria…is not chosen’.[17] However, a person’s behaviour choices may have an impact on the intensity or otherwise of their feelings.

For the person suffering from gender dysphoria, there are no easy pathways. Gender dysphoria is often accompanied by concurrent mental health difficulties (notably depression and autistic spectrum issues) and attempted suicide has unusually high prevalence among those suffering from gender dysphoria. If living with gender dysphoria is difficult, for those who pursue transition, the challenges are many. Transition is always incomplete: as Dr Paul McHugh, formerly psychiatrist-in-chief at Johns Hopkins University, wrote ‘People who undergo sex-reassignment surgery do not change from men to women or vice versa. Rather, they become feminized men or masculinized women.’[18] A trans male can never father children and a trans female can never bear children. Personal relationships are complicated by the hinterland of pre-transition life: to conceal results in deception and lack of intimacy, to reveal risks misunderstanding and rejection.

While radical hormonal and surgical interventions, and puberty blockers for prepubescent children, are deployed in medical contexts, it is notable that the research available to assess, let alone support, such procedures remains limited. There are few, if any, longitudinal studies, with statistically significant sample sizes, and control groups to demonstrate clear therapeutic benefits.[19] A recent NHS publication on Gender Identity Clinics stated: ‘There are currently no agreed measures of success or patient outcome measures. This makes determining good patient care…very difficult.’[20]

Radical agendas and transgender ideology

Transgender activists recognise that the medical model of gender dysphoria has been useful in arguing for the social acceptance of transgender people, funding therapies through the NHS or insurance, and accommodation under the law.

However, for transgender activists it has limitations: ‘the medical approach to gender variance, and the creation of transsexuality, has resulted in a governance of trans bodies that restricts our ability to make gender transitions which do not yield membership in a normative gender role. The self-determination of trans people in crafting our gender expression is compromised by the rigidity of the diagnostic and treatment criteria.’[21]

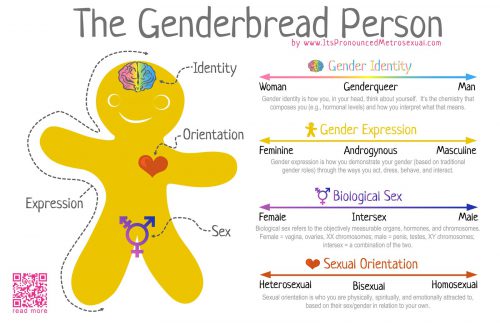

The transgender movement has a radical agenda to foster a revolution in the way we understand gender: seeking to displace a binary understanding with one in which a person may embrace a third gender, or many genders, or no gender, or a fluid and changing gender. We see this in educational material being made available to primary and secondary schools by organisations such as Stonewall, Gendered Intelligence and Educate & Celebrate.[22] In the US a diagram of the ‘Genderbread Person’ is used to highlight the spectrum of possibilities available to everyone.

We see this in campaigns to change the law in relation to transgender persons. Under the Gender Recognition Act 2004 a person over 18 may apply for a gender recognition certificate which, if issued, changes their legal gender for all purposes and so leads to the sex on their birth certificate being changed.[23] An applicant must show he/she has gender dysphoria, has lived in the acquired gender for at least two years and intends to do so until death, and has the support of two medical/psychological reports. Under the Equalities Act 2010, direct or indirect discrimination against a person with the protected characteristic ‘gender reassignment’ is prohibited. A House of Commons Report on Transgender Equality[24] recommended a major change of approach:

- Gender recognition should be based on ‘gender self-declaration’ and anyone over 16 should be able to make an application;

- The Equalities Act 2010 should be amended so that the protected characteristic is ‘gender identity’ defined as ‘each person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender…’;

- Official records should be ‘non-gendered’ as a general principle. The Government was invited to consider the creation of a legal category for people with a gender identity outside the male/female binary.

While the Government is committed to developing a new action plan for transgender equality, to a review of the Gender Recognition Act, and to ‘driving progress towards a society…where everyone is free to be themselves’,[25] in various areas it has called for more evidence for the case for change.

These policy debates echo the important distinction between a medical condition (gender dysphoria) and an ideology seeking radically to transform understandings of gender and society (transgenderism). Recent decades have seen a growing gap between ‘law’ and ‘nature’ as legal frameworks for in vitro fertilisation and surrogate motherhood, and recognition of same-sex marriage, have arisen. ‘Gender self-declaration’ would go further still and be tantamount to the disappearance of the body in the eyes of the law.[26] While Christians should be among those most concerned to bring an end to bullying and harassment of people whose gender expression is unconventional, the radical changes proposed by those promoting a transgender ideology are deeply troubling. This is identity politics in a new guise, promoting a social revolution for which there is no historical precedent, and which risks the proliferation of ‘gender confusion’.

Some biblical reflections

An embodied life

In the creation accounts, themes of identity, bodily existence, sex, marriage, and gender roles are all woven together. If feminism prompts discussion of whether gender distinctions based on sex differences do exist (as regards abilities and attributes) or should exist (as regards social roles), transgenderism raises new concerns. Here, the relationship between ourselves and our bodies, between our physical sex and our gender (however understood), and questions of personal identity take centre stage.

The creation accounts emphasise our materiality (as the man is formed from the dust), affirm the physical differences of the man and the woman as each is created in a different way, and conclude by celebrating our physicality (‘This is now bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh’). Thus, ‘bodies are not things we inhabit, but the way we inhabit the world as the kind of creatures God has made us.’[27] Our bodies teach us we are dependent, not autonomous, and signal that we are made for relationships of reciprocal self-giving.

Moreover, in the biblical view of the human person, although body, mind, heart and soul can be distinguished, each of us is meant to be a united whole, or psychosomatic unity, rather than divided parts.[28] From a biblical perspective, gender is neither detachable from biology nor merely a matter of biology. There is, or is intended to be, an organic unity of biological sex and gender identity. By contrast, the view that my inner self is paramount and I am free to shape my body to reflect my inner self has parallels with Gnosticism. Paul confronted the outworking of Gnostic views in his day: sexual licence (if the body is unimportant I am free to do with it as I please) and asceticism (if the body is unimportant I should treat it harshly). Instead, the body is the ‘temple of the Holy Spirit’ so we should ‘honour God with [our] body’.[29]

‘Male and female he made them’

The human race is made in the image of God and made ‘male and female’ – two sexes which are neither identical nor interchangeable. The Genesis account exults in the abundant diversity of God’s creativity but the theme of binary distinctions, as God creates and separates, is woven into his handiwork (in light and darkness, water above and below the sky, land and sea, sun and moon, male and female).

There is another way in which the Creator/creature distinction is profoundly important in relation to matters of sex and gender. Our physical sex is a ‘given’ which we may be able to mask but ultimately cannot change; and our sex, as male or female, comes as a ‘gift’ from God, neither earned, nor made, nor chosen by us. It is a gift which comes to us out of God’s generosity and goodness and, as Oliver O’Donovan puts it, as a gift we can either embrace or resent.[31]

In Matthew 19, Jesus affirms the binary division of the human race into male and female as the Creator’s intention, yet moments later he says that some are born eunuchs, some are made eunuchs and some choose to be eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom.[32] The context is a discussion about marriage and divorce, so eunuchs are not presented as a ‘third sex’ but as those who cannot (or do not) marry and have children. Today, still, sometimes nature goes awry (in intersex conditions) and society has motives for reshaping a person’s body (through sex reassignment surgery). Christians can at times affirm male/female distinctions as normative in a way that, with insensitivity, brushes aside the reality of lives with a complicated relationship with those categories. However, as the example of Jesus shows, it is possible to uphold the reality of a divine pattern (rather than bowing to contemporary pressure to reinvent theological understandings of sex and gender) while making space in our thinking for people and situations which do not fit tidily into that pattern. Interestingly, when the gospel spread beyond Jerusalem, the first convert brought to our attention is the Ethiopian eunuch.[33]

Gender distinctions through salvation history

The theme of maintaining gender distinctions finds expression in a number of ways as the Bible unfolds: men should not act sexually as women or dress like women, and when men and women adopt other-gendered expressions of identity, Paul refers to it as a ‘disgrace’.[34] Some claim that when Paul says there is ‘neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus’,[35] he refers to a telos where male and female will cease and encourages a realised eschatology where the undoing of male and female in the present is a redemptive act, the removal of identity categories that hold people in bondage.[36] But this ignores the context of Galatians 3:28, where access to salvation apart from the law is the concern, and clashes with Paul’s sustained respect for gender distinctions elsewhere in his letters. Nonetheless, it must be appreciated that whether or not we will have bodies with differentiated sexual characteristics in the new creation is not made explicit in the New Testament. We do know that there will be no marriage and we will be like the angels [37] but beyond this lies a degree of uncertainty. However, the persistence of sexed bodies from creation, through the fall, and beyond the cross as a central component in human identity, and the NT emphasis, especially in 1 Corinthians 15, on continuity of body, soul and identity, favour the view that we will have sexed bodies in the new creation.

The Fall and the pathway to salvation

The wide-ranging effects of human sin affect our relationship with nature and our own self. The human person is intended by God to be an integrated whole but human sin leads to ‘dis-integration’, to ‘suffering’ and to creation enduring ‘frustration’ and ‘bondage to decay’.[38] The Fall lies at the root of both the causes of, and many of our responses to, many types of dysphoria (feelings of distress), including gender dysphoria.[39] If there is a ‘givenness’ to our gender, there is also a ‘brokenness’ to our experience of gender – a brokenness in which we all share in some way or another.

Faced with ‘gender confusion’, we should remember Paul leads us to expect that in a culture which pushes God to the margins of life and ignores divine revelation, God will allow our minds and hearts to mislead us – especially in relation to spirituality and sexuality.[40] The outworking of the human race’s rebellion against God can go beyond rejection of God and his moral law and spill over into a rejection of ‘nature’ as made by God. It is not fanciful to ask whether, consciously or unconsciously, sex reassignment procedures amount to an attempt to usurp the role of creator.

For the Christian, while our hearts and minds begin to be transformed here and now, this side of heaven we ‘groan inwardly as we wait for the redemption of our bodies…’.[41] The gospel ‘brings hope that the God who made us male and female can realign distorted identity and bring increasing coherence between sex and gender, even if such healing may not always be fully realised in this life.’[42] The pathway of Christian maturity is often one of learning to honour Christ in the midst of our struggles. It is in the new creation, when we will receive new resurrection bodies, that God will wipe every tear from our eyes, and there will be no more pain.[43]

Identity in creation and Christ

We should not be surprised that people seek a pathway to meaning and identity, and will go to great lengths in pursuit of these goals. We are finite creatures and the shadow of insignificance hangs over us: ‘What is man that you are mindful of him?’ Yet the Psalmist realises God has ‘crowned us with glory and honour’.[44] He gains this insight not through introspection, philosophical speculation, or an effort to build a ‘name’ for himself, but in the context of humble adoration of the God who made him. To recognise that we are made in the image of God, humbles us (we are merely an ‘image’) and gives us dignity (we are made in the ‘image of God’). The Christian receives a new identity in union with Christ.[45] This identity is personal (as Jesus calls his sheep by name), eternal (chosen by God before the creation of the world, our story did not begin with our conscious experience of ourselves or our gender), dynamic (as we are transformed into the likeness of Christ as we work out our salvation) and relational (as we become children of God and join the household of believers, a holy nation, a royal priesthood).[46]

Perplexing dilemmas

Gender dysphoria and the transgender movement give rise to many perplexing dilemmas, and difficult pastoral issues that barely existed a few years ago will confront churches.[47] There is the challenge of extending compassion to those who suffer from gender dysphoria, gently guiding those caught up in ‘gender confusion’, showing respect to people with radically different views and lifestyles, and – at the same time – combatting the radical claims of the transgender ideology. We can see how language is a key arena: one in which confusion has grown and through which cultural shifts are revealed. One emerging flashpoint is the topic of ‘preferred gender pronouns’. At the University of Toronto, Dr Jordan Peterson recently prompted a firestorm of controversy by refusing to use alternative pronouns as requested by trans students and staff, such as the singular ‘they’ or ‘ze’ and ‘zir’. It is reported that his employers have warned that, while they support his right to academic freedom and free speech, he could breach the Ontario Human Rights Code for his refusal, and that students and faculty have complained that his comments are ‘unacceptable, emotionally disturbing and painful’.[48] Should Christians follow Dr Peterson’s example?

Christians must be committed to compassion (for those who experience painful alienation from their bodies) and to truthfulness (in the face of flawed accounts of gender identity). The principles that we should avoid unnecessary provocation but be willing to embrace necessary provocation are likely to be helpful.[49] With forethought and skill, conflict can often be sidestepped by avoiding the use of third-person pronouns. However, some argue that if third-person pronouns are unavoidable, Christians must take seriously the fact that language is the gateway to truth and not use pronouns which promote a false understanding of gender identity. It may be accepted that names are less clear cut: one may know someone has transitioned but not know their original name, and the link between names and gender is less direct.

However, caring for individuals suffering from gender confusion and publicly challenging the transgender ideology may be in tension: the former requiring building relationship and trust over time before the sensitive topics of names and gender identity can be addressed; the latter resistance to the reshaping of language. But the view that one should only use the pronouns referable to a person’s birth sex (whether out of commitment to truth-telling or as an act of integrity to one’s own convictions) may run into conflict with legal obligations to employers or the state. There is a place for civil disobedience, regardless of the cost, but not all Christians will be convinced that this issue calls for it.

If language is a presenting issue, at the heart of the many questions raised by the transgender ideology lies the question: ‘What does it mean to be a human being?’ As Pope Benedict XVI put it:

The very notion of being – of what being human really means – is being called into question… According to this philosophy, sex is no longer a given element of nature, that man has to accept and personally make sense of: it is a social role that we choose for ourselves, while in the past it was chosen for us by society. The profound falsehood of this theory, and the anthropological revolution contained within it is obvious. People dispute the idea that they have a nature, given by their bodily identity, that serves as a defining element of the human being.[50]

The transgender experience is more than, but not less than, a window into our restless spirits. In the TV series Humans, the experience of ‘synths’ (synthetic humans) endowed with ‘consciousness’ by special code allows the scriptwriters to reflect on the human predicament. The synth Mia says: ‘I want to know who I am, not what I was made for, but what I can become…’. Mia gives voice to the search for identity and to contemporary resistance to the idea of a ‘given’ identity.

Christians know that the gospel is both a free gift (salvation offered at Christ’s sole expense) and offensive (as we are completely unable to earn our salvation). A challenge for Christian apologists is how to make the idea of identity as something we receive, in creation and in Christ, one that is appealing rather than unwelcome in an age that prizes autonomy so highly. And yet, as C. S. Lewis says, as long as I resist God and try to live on my own, the more I become ‘dominated by my own heredity and upbringing and surroundings and natural desires… It is when I turn to Christ, when I give myself up to His Personality, that I first begin to have a real personality of my own.[51] Like so much of the gospel, there is much here that is counterintuitive, and which calls us to deeper reflection, and to seek divine aid, if we are to communicate profound truths in a compelling way in our own age.

Christopher Townsend is a solicitor based in Cambridge who specialises in employee share schemes and tax for companies and their owners. He is married to Kate, a GP in Cambridge with growing numbers of patients exploring questions of gender identity, and they have three children. He serves as secretary to the Cambridge Papers Editorial Group.

This article first appeared on the Jubilee Centre website and was republished with permission.

[1] R. A. Mohler, We Cannot Be Silent, Nelson Books, Nashville, 2015, p.69.

[2] Buzz Bissinger, ‘Caitlin Jenner: The Full Story’, Vanity Fair, July 2015, www.vanityfair.com.

[3] L. S. Meyer & P. R. McHugh, Sexuality and Gender, The New Atlantis – Special Report, No 50, Fall 2016, p.94.

[4] S. Baron-Cohen, The Essential Difference, Penguin, 2004.

[5] S. de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, New York: Bantam, 1952, p.249.

[6] ‘The Social Construction of Gender’, Boundless Sociology, Boundless, 26 May 2016. Retrieved 15 Nov. 2016 from https://www.boundless.com/sociology/textbooks/boundless-sociology-textbook/gender-stratification-and-inequality-11/gender-and-socialization-86/the-social-construction-of-gender-496-8675/

[7] J. Butler, ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory’, Theatre Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4, Dec. 1988, pp.528 (available at www.amherst.edu).

[8] J. Coffey, Life after the Death of God? Michel Foucault and Postmodern Atheism, Cambridge Papers, Vol. 5, No. 4, December 1996.

[9] See the Preamble to The Yogyakarta Principles on The Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity at www.yogyakartaprinciples.org. Accessed 27 Nov. 2016.

[10] NHS Choices: Your health, your choices, www.nhs.uk.

[11] See M. Yarhouse, Understanding Gender Dysphoria, IVP, 2015, p.92. It is possible that prevalence rates could change over time.

[12] A. Flores et al, ‘How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States?’, Williams Institute, UCLA, 2016, p.7 at http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many- Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf.

[13] A 2012 survey by the Equality and Human Rights Commission cited in CR181 ‘Good practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of adults with gender dysphoria’, Royal College of Psychiatrists, October 2013.

[14] M. Yarhouse, op. cit., pp.105 citing Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

[15] M. Yarhouse, op. cit., pp.95–98.

[16] M. Yarhouse, op. cit., pp.61–83 and L. S. Meyer & P. R. McHugh, Sexuality and Gender, pp.98–114.

[17] M. Yarhouse, op. cit., p.81.

[18] P McHugh, ‘Transgender Surgery Isn’t The Solution’, The Wall Street Journal, Updated 13 May 2016 (accessed 27 Nov. 2016).

[19] See, e.g., M. Yarhouse, op. cit., p.119 and see L. S. Meyer & P. McHugh, op. cit., pp.108–113 for a discussion of a number of available studies.

[20] ‘Operational research report following visits and analysis of Gender Identity Clinics in England, November 2015), p.38.

[21] Spade, Dean, ‘Mutilating Gender’ in The Transgender Reader, eds. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle, Routledge, quoted in ‘Postgenderism: Beyond the Gender Binary’ by George Dvorsky and James Hughes, March 2008). Accessed on 16 Nov. 2016 at www.ieet.org/archive/IEET-03-PostGender.pdf

[22] Some examples are noted in The Christian Institute’s briefing paper Transsexualism at www.christian.org.uk.

[23] In the last decade, fewer than 4,500 people have legally changed their sex by obtaining such a certificate (see ‘Debate on “Transgender equality” 1 December 2016’ at www.christian.org.uk)

[24] House of Commons Women and Equalities Commission, Transgender Equality, First Report of Session 2015–2106, London: The Stationery Office Limited, January 2016.

[25] Government Response to the Women and Equalities Committee Report on Transgender Equality (Cm 9301), July 2016, p.5.

[26] D. Moody, The Flesh Made Word (Expanded Edition), 2016.

[27] A. Sloane, ‘Male and Female He Created Them’? Theological Reflections on Gender, Biology and Identity,Ethics in Brief (Vol. 21, No. 4), Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics, Summer 2016. Available at www.klice.co.uk, p.3.

[28] The unity of the person implies functional holism and is compatible, for example, with integral body–soul dualism and does not deny an intermediate state between death and bodily resurrection.

[29] 1 Cor. 6:12–20; 1 Tim. 4:1–4.

[30] Eph. 5:21–33.

[31] O. O’Donovan, Begotten or Made?, OUP, 1984.

[32] Matt. 19:1–12.

[33] Acts 8:26–40.

[34] Lev. 18:22; Rom. 1:18–32; 1 Cor. 6:9–10; Deut. 22:5; 1 Cor. 11:14–15.

[35] Gal. 3:28.

[36] See, e.g., discussion in M. K. DeFranza, Sex Difference in Christian Theology: Male, Female and Intersex in the Image of God, Eerdmans, 2015, pp.246–259.

[37] Matt. 22:30.

[38] See Rom. 8:19–27.

[39] Some evangelicals caution against too hasty an association between non-standard biological variations (which could include neurological variations in the brain) and the Fall as the normal functioning of our DNA involves the existence of biological variation as an intrinsic feature of bodily existence.

[40] Rom. 1:21–22.

[41] Rom. 8:23.

[42] ‘Gender Dysphoria’, R. Thomas & P. Saunders, CMF Files No 59, p.5 (available at www.cmf.org).

[43] Rev. 21:4.

[44] Ps. 8:5.

[45] 2 Cor. 5:17.

[46] John 10:3; Eph. 1:4; Phil. 2:12–13; Eph. 2:19, 1 Pet. 1:9.

[47] A short, helpful book written by a pastor is Vaughan Roberts, Transgender, Good Book Company, 2016.

[48] ‘Toronto professor Jordan Peterson takes on gender-neutral pronouns’, 4 Nov. 2016, www.bbc.co.uk (accessed 27 Nov. 2016).

[49] Denny Burk: ‘Bruce or Caitlyn? He or she? Should Christians accommodate transgender naming?’, www.dennyburk.com (accessed 17 Nov. 2016).

[50] Quoted in D. Burk, What is the meaning of sex?, Crossway, 2013, p.158.

[51] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Fount, 1977, pp.187–88.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Jubilee Centre - Gender: where next?