Mission from the margin in Kosovo

Christian alienation is not, by definition, a negative consequence of being Christian or an unintentional aspect of Christian life.

18 SEPTEMBER 2018 · 17:09 CET

‘Christianity as default is gone: the rise of a non-Christian Europe’, was the title of a recent article.1

We see this kind of message in publications with some regularity, but it struck me that this research was all about young people aged 16-29. I asked myself, a bit skeptically, ‘what will the future church look like?’

I can imagine from a Christian perspective, this is often exactly how the decrease of Christianity is seen. It feels painful and we feel skeptical. What will the church be in the future?

But then, in the same article, another sentence struck me: ‘In 20 or 30 years’ time, mainstream churches will be smaller, but the few people left will be highly committed.’2 Small in number, but highly committed.

The church in the margin, as minority, but faithful present in the society. The aspect of Christian alienation might help us to understand the decreasing position of the church in a more healthy and positive way.

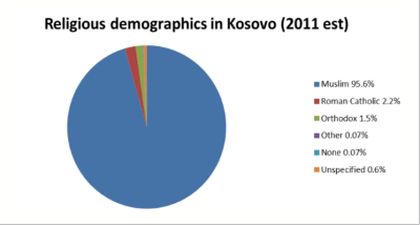

In this article we will look at 1 Peter 1:1 and at the Protestant-Evangelical movement in Kosovo. This church exists in the context of Islam, and has already been in the margins for decades.3

In the beginning of 1 Peter we see the author of the document calls his readers: ‘God’s elect, strangers in the world, scattered’. (NIV) There are three elements in this verse which relate to Christian alienation: Identity, Estrangement and being scattered.

I will describe each and include some modest comments related to the church of Kosovo to give us possibly a more optimistic and hopeful view on the future of the Christian movement in the margins.4

IDENTITY OF THE CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT

Why are Christians alienated on earth? It seems logical to say that this is a consequence of being Christian. But, in my humble opinion, it is often seen as an unintended – and even maybe unwanted – consequence. It might have negative associations.

We do not long for Christian alienation. But in 1 Peter 1 Christian alienation is related to God’s sovereign love. The author speaks about God’s election and this makes the church a movement of strangers.

Because of God’s sovereign love he has chosen the movement of Christians as His representatives on earth.5 So, if this is the case, Christian alienation is not, by definition, a negative consequence of being Christian or an unintentional aspect of Christian life.

No, it is just a positive consequence of being chosen and intentional in nature. This is a radical other perspective which might be often overseen.

This consideration can be helpful for churches in the margins. In Kosovo for example, Christians have to face social persecution.6 There is tension within their families because they become Christians.

Gossip, insults and disdain occur regularly. But, despite these difficulties which I don’t want to downplay, they may see that alienation, with all the challenges and difficulties, is intentional and a consequence of being chosen through godly love.

That’s why Paul said: ‘You are no longer foreigners (…), but fellow-citizens with God’s people and members of God’s household (…) with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone.’7 Such a clear identity gives a great comfort in all circumstances for the church in Kosovo as well for all churches all over the world.

ESTRANGEMENT

The author of 1 Peter speaks about ‘strangers’. What does this mean?

First of all: believers are mentioned as strangers in this world. This because of their calling to live a holy, i.e. distinct, life.8 This holiness makes them different from their environment, because of their identity, because of their calling to live a holy life.

This difference is twofold in nature.

1) Christians feel themselves different in their own environment. This gives an inner estrangement to a non-Christian context. But the distinction also works the other way around.

2) The non-Christian context sees Christians as strange because they have other convictions and they behave differently. The latter one is an external perspective.

In relation to the external perspective Christians in Kosovo are often seen as foolish and even as traitors. This has to do with historical tensions between Serbs and Albanians. Kosovar Albanians know that Serbs are (Orthodox) Christians.

From their perspective, the Christian Serbs killed and raped a lot of Albanians during the war at the end of the 90’s.9

With regard to the inner perspective Christians do face the fact that they have to behave differently. On the one hand they keep some distance and on the other hand they try to reach to their own people.

This paradoxical attitude, inspired by the notion of Christian alienation, raises the question of how to protect the churches’ identity and at the same time try to be of value within the public sphere?

Christians have to live their lives in the seemingly contradictory position of neither distance nor assimilation. Alienated but as seed in their environment.

SCATTERED

According to 1 Peter, Christians are apparently scattered in their non-Christian environment. This translation emphasizes the notion of being a minority or at the margin of a society.

A movement which is scattered has no religious or political power. In Greek the term ‘diaspora’ is used. This also reminds us about the exile experience of the people of Israel during the Old Testament. What was one of the characteristics of the exile? Longing for their home, Canaan.

So, somehow Christians have a kind of diaspora experience.10 They are longing for their home country,11 the eschatological reality with God, and powerless in the earthly reality.

In Kosovo there is no Christian political movement, no Christian lobby, no big churches. In Kosovo we have only Christians who live their lives and share their hope within their families, within their villages.

They share their hope for a future reality, but also hope for their country in this earthly reality. There is no room for any kind of escapism. And just in this paradoxical engagement they live their godly missional lives.

Godly lives, in the margin, in a non-Christian society. And from the margins Christians try to live in the midst of their (non-Christian) neighbors. Not as victims, but as victors, as chosen people. Alienated on earth, but not alienated before God.

I know; Christianity as default is gone, but I see the rise of a church in the margin in a non-Christian Europe. Right there where God called the church to be.

Rik and Matched Lubbers are ECM missionaries who have worked in Kosovo since 2013.

This article first appeared in the September 2018 edition of Vista magazine.

Endnotes

1. Sherwood, H., ‘Christianity as default is gone: the rise of a non-Christian Europe’ in: The Guardian, 21 March 2018. See: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/21/christianity-non-christian-europe-young-people-survey-religion (Last consulted on 4-6-2018) Compare also: Bullivant, S., Europe’s Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014-16) to inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops (London: St. Mary’s University, 2018)

2. Ibid

3. Because of the given space I cannot work out all the Bible passages related to ‘Christian alienation’. I chose the first letter of Peter because it is just this letter that turns a marginal indication of Christian alienation to a more prominent quality of the church. Cf. e.g. Gen. 23:4; Ps. 38:13 [LXX: 39:12] and Hebr. 11:13. At the same time we recognize that this designation of the Christian movement never had a central place in the NT. It is just one of the designations for the church.

4. Christian alienation contains a lot more, but for this contribution I have to limit myself.

5.. 2 Cor. 5:20. We deliberately use the terms

‘church’ and ‘Christian movement’ alternately to

emphasize the church as collective.

6.. With social persecution I do mean social tensions which expresses as e.g. discrimination, tension within families, disadvantaged positions on the labour market etc. In Kosovo is, as far as we know, no physical persecution.

7.. Eph 2:19.

8.. Cf. e.g. 1 Pet. 1:15, 16; 2:5, 9.

9.. The difference between the Serbian orthodox church, the catholic church and the protestant church is often unknown in Kosovo. I want to emphasize that it is, in no way, our intention to interfere in any political debate related to the existing tension between Serbs and Kosovar Albanians.

10. I am careful in using the notion of ‘exile’ for the Christian church. This has mainly to do with the fact that the exile was in the OT a punishment and judgement from God.

11. See e.g. 1 Pet. 1:4.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Vista Journal - Mission from the margin in Kosovo