Biblical evangelism - then and now

Paul was “explaining” his message. This implies a two-way dialogue, because you can only know if you are adequately explaining something when you get feed-back.

23 JULY 2015 · 12:25 CET

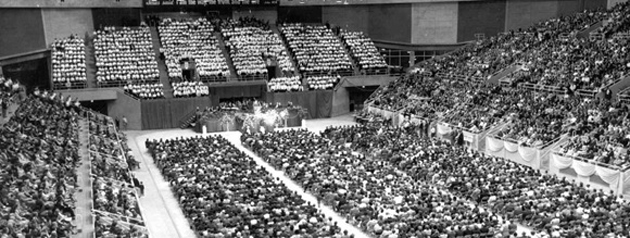

I became a Christian at the age of 20, in the run-up to a major “Crusade” in London with the great American evangelist, Billy Graham. I say “great” advisedly. Billy made an enormous impact on Great Britain for over 30 years in the middle of the last century. His team came in like a whirlwind again and again, and everyone knew about it. The publicity was relentless and it repeatedly hit the TV screens and the front pages of national newspapers. Countless thousands heard him preach, mainly in enormous stadiums, filled to capacity.

So I was in the crowd when he arrived in 1966. With more than 1,000 others, we gathered in that great cathedral of Waterloo Station, singing at the tops of our voices, “To God be the glory, great things he has done,” as Billy got off the train from Southampton. It was a wonderful reception! The Greater London Crusade was held at the vast exhibition centre at Earl’s Court and lasted a month. Nearly a million people attended and some 40,000 came forward for “counselling”.[1] The final event was held in Wembley Stadium which was filled to capacity with 94,000 people – I was there, though I did not count them myself!

I want to emphasise these statistics at the outset, because, while I had some misgivings about the style and flavour of what was going on, no one can gainsay what he achieved. Billy has faced many critics, but for my money, he always had the final, unanswerable put-down. In quoting D.L.Moody, he would say, “I prefer the way I do it to the way you don’t!”

What then were my misgivings? Although I had been a Christian for only six weeks, I had read the New Testament through carefully three times. What worried me was the atmospheric mismatch. A Billy Graham Crusade seemed so contrived and so unlike what happened in the New Testament. “This” was not “that”. It wasn’t so much the theology that troubled me as the ambiance and the context. There was no slick organisation in the New Testament; events seemed to just happen.

People at Earl’s Court made their responses on the basis of the unquestioned assertion, “the Bible says”. No justification was given as to why the Bible should be believed. Christianity was presented as a circular argument from an authoritative book, rather than a linear argument from historical data. It therefore invited a blind “leap of faith”.

In the New Testament, there were no gathered choirs stirring the emotions as people made their decisions, or long, silent psychological pressures upon them as Billy waited for them to “get up out of their seats and come forward”. In the New Testament it seemed much more spontaneous. People just became Christians. There was no platform in the New Testament, built six foot above contradiction, to protect the speaker. Evangelism then happened cheek by jowl. So the question I was left with was, “How should we do evangelism today?”

As a result, I went on various “how to” evangelism courses – but always came away with the same anxiety. This was not that either! A set of Bible memory verses, valuable as they were, hardly cut the mustard; neither did diagrams that could be drawn on paper napkins, though they could sometimes be useful! Booklets such as the Four Spiritual Laws did not bridge the gap and neither did guest services in church, particularly when the guests were invited with everyone else to stand and recite the Apostle’s Creed before they had even heard the sermon! There was to my mind something seriously adrift in 20th century evangelism, but I couldn’t easily put my finger on it. None of this seemed to be quite like that!

When she spoke at the CU, large numbers of students came to hear her.

One day, in the large common room where 250 medical students were prone to gather, a girl in my year called Mary asked if we could have a chat. We pulled up a couple of chairs and she asked me to explain what Miss Crouch had meant when she talked about being “born again”. Mary told me that her father’s family were Presbyterians, her mother’s were Methodists, and she had been sent to a Catholic school. Yet no-one had ever told her she must be “born again”!

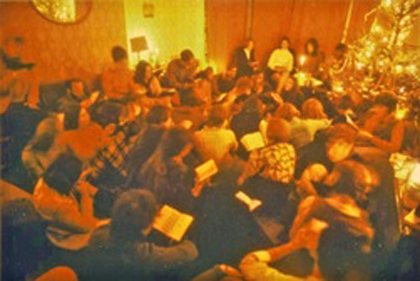

Clumsily, I started to respond. I had only been a Christian for eighteen months, and had to think carefully what to say. As I did so, another student butted in with a question, and as I dealt with that, some else joined in. Within a few minutes, several were engaged in our conversation and more joined us. They pulled up chairs or sat on the floor, some engaged vocally, others stood around listening, until some twenty or more people were engaging with me.

I was always struggling, wrestling to deal with so many diverse questions. Conversations went “every which way” – some scornful, some interested, but everyone thoughtful. As issues were flying around left, right and centre, I had the great realisation that “this was that”. This is what was going on in Capernaum, in Jerusalem, in Athens and in Rome. This is what I had read about in the market place of Corinth and the lecture hall of Ephesus. It was lively, spontaneous, uncontrolled - perhaps even risky.

After some 25 minutes of hub-hub, the bell rang giving us five minutes warning that the afternoon sessions were about to begin. Everyone quickly scooped up their bags and books and headed for the doors, leaving me sitting with Mary.

I turned to her and apologised. “I am sorry. I was completely distracted. I not only haven’t answered your question, I can’t even remember what it was!” She replied quietly, “That’s OK. It doesn’t matter.” “But surely it does?” I insisted. “No, it doesn’t. I wanted to know what it meant to be ‘born again’. It doesn’t matter anymore.” “Why is that?” I asked. “Well, I just have been. What do I do now?”

I was taken aback and rummaged in my case to find a copy of John Stott’s book, Basic Christianity. “I suggest you read this.” To my surprise, the following day Mary returned the book to me. “I have read that. Now what do I do?” Mary was a bright student and evidently a fast reader. “Read John’s Gospel,” I said, “and come to church with me on Sunday to hear John Stott preach.

Mary eventually married one of my flat-mates and they returned to his native Australia, where they have been involved in Christian mission ever since. Whenever they come to Britain, we try to get together. Their eldest daughter and her family are currently missionaries in Indonesia. Nearly 50 years on, Mary is still going strong. Her life was turned around in that brief, chaotic discussion.

She was a large personality – in various ways! She was an extrovert and well known in our medical student community. People saw the change in her. As a result of her conversion, a steady trickle of students became Christians. A couple of months later, I asked another student, a professing atheist, what she thought about Christ. I was expecting an intellectual response, but she suddenly welled up with tears! (Women! Why do they do that?) But what she said is written indelibly on my mind: “How can I not believe? Five of my closest friends have become Christians. They have found a joy in life they never had before. They have found meaning and purpose in life.”

In fact, so many people had become Christians that I was never able to work out who her closest friends were! Within eighteen months, our CU group had grown from 10 to 50. Recently, the intake of 1967 had a reunion, as one does after 46 years! (Such parties don’t need an excuse – all they need is an organiser!) It was well attended and I could not identify anyone there who had stood as a Christian all those years ago but had given up on Christ since. They still bubbled with enthusiasm and commitment as we caught up with each other’s stories.

Looking back, the unbelievers had found it all very difficult to understand. The student newspaper carried many interesting comments. The only way they could understand the change in behaviour of those who had become Christians, was that there had to be some kind of CU Police Force at work. The CU members didn’t get drunk. They didn’t cheat or swear. The girls didn’t flirt and the men were not womanisers. So they developed the idea that student parties were being infiltrated by a secretive CU Police, who presumably wrote down names, or whispered warnings in Christian ears. They must also have organised a curfew, as the Christians never seemed to stay out late! They had no other way of understanding the transforming work of the spirit of Jesus in the lives of his followers.

So what did this teach me about evangelism? Well, I am sure that humanly speaking, the Gospel ran through our pre-clinical students because we were a tight-knit community. When someone became a Christian, it was noticed by others, and as we studied the Bible together and were able to encourage one another in our Christian discipleship.

But as with that discussion in the Common Room, sharing the Gospel was spontaneous and infectious. Questions were openly discussed. Yes, helpful talks were given and good books – especially those written by Michael Green - were distributed and read. But the Gospel spread largely from person to person, in an informal way. Conversations were happening everywhere, not least at the dissecting tables around dead bodies!.

It took me some time to identify what I now see as the pivotal issue. If you look at the “action” words in the New Testament, that is, the verbs describing what the apostles were doing, English translations are rather misleading. Again and again, the apostle Paul is described as “reasoning” with people. This sounds somewhat dry, academic and intellectual. Not knowing any Greek, I had no idea what the Greek verb translated as the “to reason” actually implied. Most English versions use this same word. So Paul “reasoned” with the Jews at Thessalonica (Acts 17:2), with both Jews and Gentiles in Athens (Acts 17:17), with Jews and Greeks in Corinth (Acts 18:4), with Jews in Ephesus (Acts 18:19, 19:8), and was reasoning daily “with all the residents of Asia” in the school of Tyrannus for two years! (Acts 19: 9,10). There are many other words that are used – he preached, admonished, testified, persuaded, declared, discussed and convinced – but the word “reasoned” is used most often and is particularly interesting.

The Greek verb is dialegomai. It means to converse, to negotiate, to discuss, to dispute [2]and it is the root of our word “dialogue”. It implies words going “across” (dia) between two people. It is used, for instance, to describe the disciples arguing among themselves as to who was the greatest (Mark 9:34). We can imagine Paul’s lively exchanges in the synagogues and in the market places “everyday with those who happened to be there.” (Acts 17:17)

Consider Paul in Thessalonica. Acts 17 tells us that Paul here adopted his normal strategy (verse 3) and this is what he did. He headed initially for the synagogue where he “reasoned” with the Jews from the Scriptures (v.3). Given what we now know about the meaning of this word, this sounds much more like a discussion in a group Bible study than the formal exposition of a text from a preacher. This was dialogue, not monologue.

Luke now uses other verbs, which draw out the full flavour of what was going on there. We are told he was “explaining” his message (verse 3). This also implies a two-way dialogue, because you can only know if you are adequately explaining something when you get feed-back. It is in understanding what they have grasped so far, and also what they have failed to grasp, that explanation comes into its own.

This is now coupled with “proving” or “giving evidence” (verse 3). This can only be achieved if one hears the doubting and scepticism that needs to be addressed. You cannot substantiate the truth of something if you have not first listened to the uncertainties about it. You then marshal your arguments to address specific questions.

It is therefore in this two-way process of dialogue that Paul identifies and addresses these three crucial areas - ignorance, misunderstanding, and doubt. And Paul himself describes this activity of dialogue as “proclaiming” Christ (v.3).

As if the picture is still not clear, Luke now says that as a consequence of

1) gaining information, 2) hearing explanations and 3) receiving evidences, that a great many were “persuaded” (verse 4). And here, Luke puts his finger on the missing word in contemporary evangelism, which we shall explore next.

Peter May is a retired medical doctor, former UCCF Trust Board chairman and lay member of Church of England's General Synod.

[1] Take 2 minutes out to see this: www.britishpathe.com/video/the-great-crusader

[2] Kittel & Friedrich,Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Translated & Abridged by Bromiley).Eerdmans 1985

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Forum of Christian Leaders - Biblical evangelism - then and now