Man’s disorder, God’s design

One colleague, Clemens van de Berg, spoke about the under-appreciated role of Protestant churches in shaping the international postwar order. This order and stability is under serious assault today.

14 APRIL 2025 · 15:55 CET

Some came from Balkan societies where war memories are still fresh. Others were studying in Bucha, Ukraine, where just three years ago over 500 civilians and prisoners of war were butchered by Russian invaders.

They were among the mainly eastern and central Europe students attending a conference held in a Dutch monastery this week on how the Gospel helped make Europe ‘Europe’.

Their event was part of the larger INCHE conference for 150 Christian educationalists from institutions around the world.

I was part of a teaching team for this Erasmus-sponsored student track covering classical, medieval and modern phases of the European story. Why were Europe’s roots important?

How did creative minorities shape society? Where did human rights come from? What were the distinctives of Eastern and Western Europe? How did the gospel shape European integration? How should the Church relate to the sphere of politics?

One colleague, Clemens van de Berg, focused on the under-appreciated role of Protestant churches in shaping the international postwar order. This took on an unexpected topical relevance given that this order and stability is under serious assault today by nationalists east and west.

Clemens highlighted a significant event which happened in 1948 just a few hundred metres from my home in Amsterdam. The inaugural assembly of the World Council of Churches sought to promote ecumenical cooperation among the national Protestant churches.

For Dutchman Willem Visser ’t Hooft, who presided over this first assembly, only a united Church could have moral authority to shepherd the European peoples toward unity.

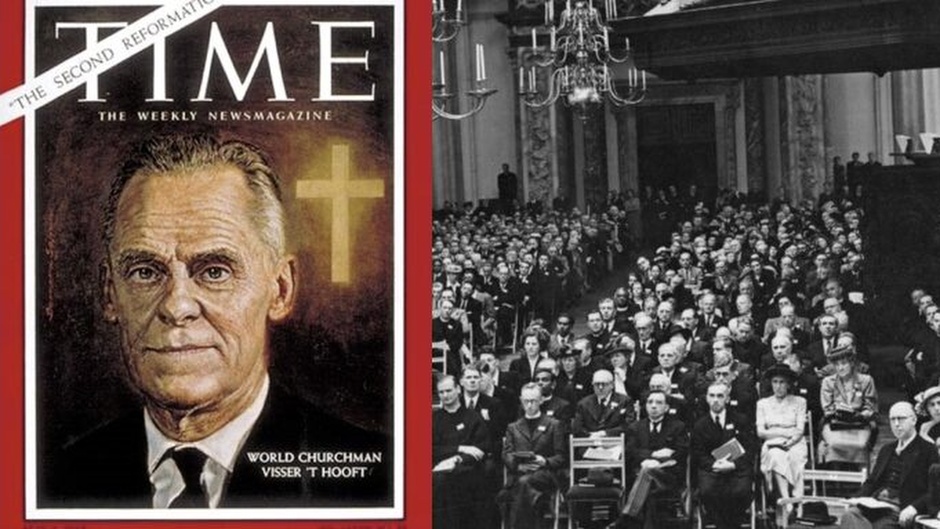

Featured on the cover of Time Magazine in December 1961, Visser ’t Hooft lamented the fragmentation of the one Church in Europe into many national churches, resulting in the Church losing sight of her task to give shape to the life of Europe as a whole.

Disrupted

The assembly had been planned originally for a decade earlier but the outbreak of World War Two had forced its delay. Actually the roots of the fledgling ecumenical movement were as early as 1910 when the Edinburgh Missionary Conference had generated widespread enthusiasm for mission collaboration. But initial partnership had been disrupted by World War One.

Two ecumenical committees were set up in the interwar years: Faith & Work (doctrinal issues) and Life & Work (social & ethical issues). Tensions began to emerge in the ’30s especially between British and German theologians about the role of the Church in the public sphere.

Growing nationalism in Germany brought pressure on the churches to understand politics as a Völkisch question (i.e. focused on Aryan ethnicity), in which the church had no say.

The British understood the inherent transnational nature of the church to imply her responsibility for international politics.

The Anglican bishop George Bell had cried: “Let the Church be the Church!” The German Lutheran bishop had responded: “The Church should not obstruct the state to establish order with harsh measures. (…) We are a Volk of order, law, and discipline.”

Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess had himself responded to Bell’s criticism of the Nazi purge of the Aryan race of ‘impure and corrupting elements’: “The German state deserves praise, not criticism from the clergy, because it has saved a nation from Bolshevism.”

I found myself replacing that last word with ‘wokism’ and ‘globalism’, and ‘German state’ with current fascist-leaning parties and governments. I thought of today’s horror stories about forced extradition of ‘impure and corrupting elements’.

And of the brave bishop who recently reminded a newly-elected president of his accountability to God. I wondered how we would assess the role of our European churches today in the public sphere.

Reminder

The scars of World War Two were still visible across Europe as church leaders from all continents gathered in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam in August 1948. Cities, towns and villages were still rising out of the ashes of destruction as tensions between East and West began to mount again. Just two months earlier, Stalin had begun to besiege western Berlin as the Cold War heated up.

Under the theme, ‘Man’s disorder and God’s design’, the church leaders now came to consider the task and message of the Church in a world twice racked by global war in three decades, and now threatened by nuclear war.

For Visser ’t Hooft, the Church was a spiritual society called to be a reminder of the Kingdom of God, to keep in check and to counteract the political societies.

His vision of an ecumenical community of churches preceded the community of peoples envisioned in the Schuman Plan that was to emerge two years later.

The Ecumenical movement has been described as a ‘poorly understood rival’ to the three big ideologies of the 20th century: fascism, communism and liberalism. None of these alternatives viewed humans as children of God bestowed with a dignity independent of any state.

That understanding was fundamental to the emergence of the international order under threat today, as articulated for example in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Jeff Fountain, Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies. This article was first published on the author's blog, Weekly Word.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Window on Europe - Man’s disorder, God’s design