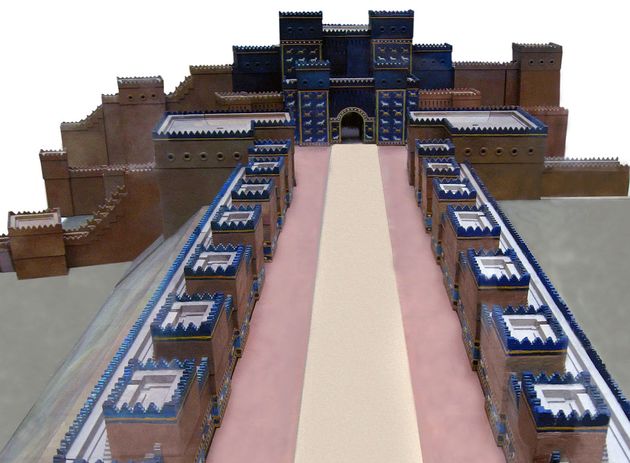

The Isthar gate and processsional way

The processional way was approximately 250 meters long, 20 meters wide and was adorned with 120 lions. The Ishtar gate hosted the festival of the Babylonian new year.

19 FEBRUARY 2020 · 13:00 CET

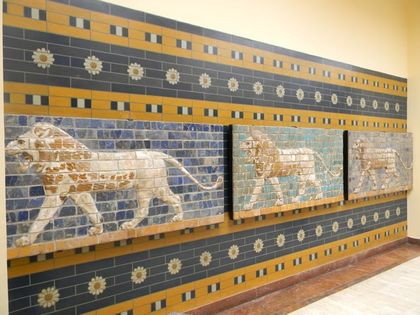

One of the most important collections housed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum is the glazed tile images retrieved from the Ishtar gate and its processional way of the ancient city Babylon.

The gate and the processional way were built during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BCE).

Robert Koldewey conducted the excavation in Babylon from 1899 to 1917 which resulted in the discovery of the double gate and the palace of Nebuchadnezzar. Currently the rebuilt gate is housed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

The processional way was approximately 250 meters long, 20 meters wide and was adorned with 120 lions. In an adjacent room the museum has in its display a cuneiform cylinder (ES 6259) which details the restoration project of the the city walls and temples in Babylon, as well as temples in Borsippa, Larsa and Sippar.

These buildings were dedicated to several gods such as Marduk, Schamasch and Ishtar. The bricks used the gate and the processional way were covered in a blue glaze meant to represent lapis lazuli.

Even though Nebuchadnezzar clearly boasts in many documents that he did indeed use the precious stone, this is not the case. Three figures are depicted in the images. The lion is connected to Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love and war.

The auroch is connected to Hadad, the Babylonian god of the storm, finally the dragon-like figure is known as “mushussu” and is supposed to represent Marduk, the chief and protective deity of Babylon.

Each of these images were strategically placed along the processional way and gates for various reasons.

The chief image in the processional is that of the lion. If you look carefully one can notice that the lions consistently keep eye contact with the beholder, the aggressive nature of this image was meant to overwhelm and intimidate those who approached the city gates.

The bull figures were connected to the storm god Hadad. Storms where a representation of blessing, for without the rain the ground would not produce fruit.

The placing of the bulls on the gates seem to suggest the idea of containing blessing within the city walls and expelling any sort of curse. The dragon figures also seem to be offering a protective role.

An inscription from a latter king named Nergilassar (560-556 B.C.) states: “I cast seven bronze savage mushussu, who spatter enemy and foe with deadly venom.” Again, this image seems to have been placed in the gates to repel any sort of evil or curse.

BIBLICAL SIGNIFICANCE

With its 100,000 inhabitants Babylon was at one point the most important and wealthy city on earth. The Jews experienced here a captivity and exile of approximately 70 years (Jer 29:10; Dan 9.2).

The exile took place with 4 waves of deportations. Prisoners of these deportations were most probably led into the city through the processional way under the menacing glances of the stylized lions.

In Biblical literature, particularly in the New Testament Babylon becomes a symbol for oppressive world powers and systems that persecute the church. In Revelation the celestial city is juxtaposed with Babylon the great. The first epistle of Peter also equates Rome with the city of Babylon (1 Peter 5:13).

Gates in antiquity where not just part of a city’s defensive system. They had high symbolic value. We know from several Assyrian documents that gates served as places for public appearances of kings and military parades.

Numerous Middle-Babylonian documents let us know that in Mesopotamia gates served as the locations where judgements were executed. The publication of legal decisions, court hearings, the testimony of witnesses, public oaths, legal transactions, and public executions all took place in the city gates.

However, the Ishtar gate was of particular importance as it hosted the festival of the Babylonian new year. In a recreation of Babylonian myths to explain the change of the year and its seasons, several gods would be lead out of the city through the river in a funeral procession meant to reflect their journey to the underworld.

After 11 days of festivity, on the 12th day the gods would be welcomed back with a cheerful parade that led the images through the processional way and the Ishtar gate. Thus the cycle of death and rebirth was complete.

Marduk and Bel (i.e. Hadad) are mentioned by name by the prophet Jeremiah:

“Announce and proclaim among the nations, lift up a banner and proclaim it; keep nothing back, but say, ‘Babylon will be captured; Bel will be put to shame, Marduk filled with terror. Her images will be put to shame and her idols filled with terror.’ A nation from the north will attack her and lay waste her land. No one will live in it; both people and animals will flee away. “In those days, at that time,” declares the LORD, “the people of Israel and the people of Judah together will go in tears to seek the LORD their God. They will ask the way to Zion and turn their faces toward it. They will come and bind themselves to the LORD in an everlasting covenant that will not be forgotten.” (Jeremiah 50:2-5, ESV)

In these verses Jeremiah gives a message of hope by reminding god’s people that the very images that are meant to protect the city will miserably fail be put into shame before Yahweh.

Following this he goes on to prophecy that the Medo-Persians will conquer Babylon and that the exiles will eventually return to Jerusalem to bind themselves in an everlasting covenant.

It is because of this prophecy that many saw in Cyrus a Messiah-like figure. For it was through his decree that the captives were able to return to Jerusalem.

These images remind us that the world is a transient place and that ultimately the powers to which this world places its confidence will eventually be put to shame before Yahweh.

Egyptian gods were put to shame through the plagues, Babylon’s images where put to shame through the Persian conquest. Eventually all worldly powers and unjust systems will be put to shame at the coming of the Messiah in the Day of the Lord.

This is the hope that the Christian clings to. It is this hope that enables the Christian to live through difficult moments and trials. The strongholds and gates of this world will one day collapse before the glory of Yahweh. And we know this is true because He has done it many times in the past.

Marc Madrigal is a Board member in the Istanbul Protestant Church Foundation in Turkey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kinker, Thomas. Istanbul. Mit der Bibel durchs Museum. 2017. Verlag fur Kultur und Wissenschaft Culture and Science Publ. 42-53.

May, N. N. (2014). "Gates and Their Functions in Mesopotamia and Ancient Israel". In Gates and Their Functions in Mesopotamia and Ancient Israel. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004262348_004

Watanabe, C. (2015). THE SYMBOLIC ROLE OF ANIMALS IN BABYLON: A CONTEXTUAL APPROACH TO THE LION, THE BULL AND THE MUSHUSSU. Iraq, 77, 215-224. doi:10.1017/irq. 2015.17

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Archaeological Perspectives - The Isthar gate and processsional way