The mysticism of Franco Battiato

The journalist Paloma Chamorro defined Franco Battiato once as “a Mediterranean artist with a penchant for orientalism, immersed in a certain religious syncretism, who likes to use symbols and allegories”.

29 JULY 2021 · 15:47 CET

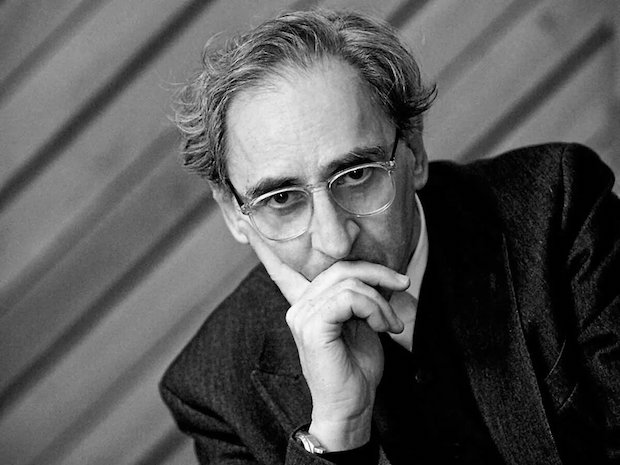

Some people don’t seem to be afraid of dying. But one thing is what people say and another what they really feel when the time comes. This was not the case of Franco Battiato (1945–2021).

And it wasn’t that he didn’t think about it, as he had actually spent most of his life preparing himself for death. He saw it as a “step” that he wanted to prepare for. In his mind it was a “transition” to an “intermediate” state, based on the idea of reincarnation, which he mixed in with Islamic Sufism or with Roman Catholicism, to which he became partly reconciled in his later years. He saw atheism as a lazy and not very intelligent position.

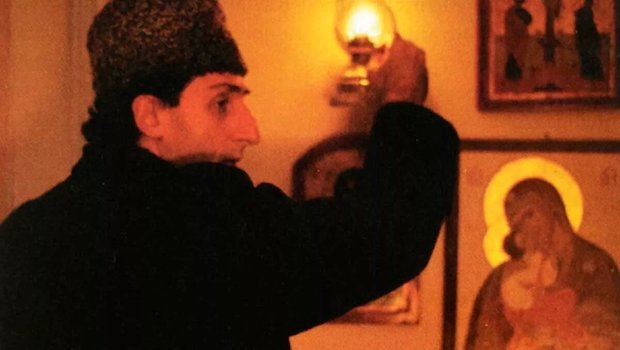

In this, as with everything else, Battiato was one of a kind, non-conformist and unpredictable. Those of us who discovered him in the 1980s only know him through the vast and multifaceted corpus of his work. In the 1970s he tried his hand at just about everything, from classical to vanguard music. He had started out in the 1960s as a melodic singer but ended up singing opera after having become a star on the techno-pop scene in the 1980s, all with his own unmistakable stamp. The Spanish journalist Paloma Chamorro, who has now also passed away, defined him once as “a Mediterranean artist with a penchant for orientalism, immersed in a certain religious syncretism, who likes to use symbols and allegories”.

Battiato was bizarre as only he could be. I liked him. What stood out for me was him imperturbable presence, his personal charm and intelligent comments. His music has great lyricism, with texts full of poetry. The air of asceticism and hermit style that he cultivated sometimes jarred with statements like “I like sex too much to live the life of a monk”. His anti-diva image was carefully curated, but it was at odds with his massive sales and the popularity with which he filled whole football stadiums in the 1980s as an eccentric pop-singer with synthesizers.

From the 1990s onwards, he had stopped being adulated by the masses. He felt a “certain fatigue with contemporary culture”, as Chamorro put it. Fascinated with the Orient, he saw himself as being “exiled in Europe”. I found his ease in all languages amusing: he was quite happy to mix his broken Spanish, English and French in with Italian, even in his own music. His interviews are a total linguistic chaos, which he himself revelled in, changing his language to suit the interviewer and taking his time to find the perfect words in each case.

Battiato said that he had his own spirituality; he was a religious man without a church.From melodic singer to experimental musician

Battiato was born in Sicily in 1945, the year that the Second World War ended, in a small village near Catania, called Jonia. As so many others of his generation, he listened to Elvis Presley and Little Richard as a boy. He asked his parents to buy him a guitar and he started his first band with a group of friends. When his father died in 1963, when Battiato was 18, he gave up his dreams of being a geologist to look for work in Milan. He worked in a shop and as a delivery boy, but he also played at street parties and in cabarets. In 1967 a scout offered to cast him as a romantic singer, which led to the recording of his first single, La torre [The Tower], followed by È l’amore [It’s love] (1968).

Phillips sold some 100,000 copies of his song Fumo di una sigaretta [The smoke of a cigarette]. Allergic to large crowds, praise did not stop him from seeing the vanity of an industry that poured itself into a trivial kind of music. He said that by 1969 he felt like a “puppet in a fake world”. He went through a crisis that submerged him in deep depression. He distanced himself from a world that he had become bogged down in, saying goodbye to festivals and ersatz culture. From the beginning of the 1970s he concentrated on research and experimentation. He bought himself sound equipment and edited five albums with the independent record label Bla Bla between 1971 and 1975. He mixed progressive rock with chamber music, creating short pieces using electroacoustics. His album Fetus is considered the first vanguard album in Italy. He dedicated it to Aldous Huxley, the author of A Brave New World.

One of the many anecdotes about Battiato is from a festival in Venice where he played one single note for more than a quarter of an hour. The audience started to boo him, but Battiato continued unperturbed. The organizers ended up making him leave the stage. He produced three more experimental albums with the label Ricordi until, in 1978, he became tired of the minimalism, the shrill sounds, the weird effects and his growing debts. It was time to reinvent himself again as a singer popular with the masses. The change was astounding. “In contrast to classical music, with pop you have four minutes in which to express yourself; a restriction that sharpens invention”, he said. His partner in this transition from vanguard to commercial music was the violinist Giusto Pio.

When eccentric pop filled stadiums

The album with which Battiato gained popularity and success with EMI in 1979 made reference to the white boar, a symbolic animal which in mythology represents spiritual wisdom. It was a collage of unconnected images somewhere between the poetic and the visionary, illustrating the collision between the modern world and the peace and tranquillity that he had always sought. He already had all his characteristic hang-ups: his Anglophobia (“on the day of reckoning, English won’t do anything for you”), the eccentricity of his sounds and his oriental exoticism. He managed to sell 15,000 copies, but more importantly, he won the admiration of an intellectual and alternative audience.

It was at that point that he began his personal and musical relationship with Alice. This attractive compatriot was born in 1954 in Forli and, like Battiato, started off as a melodic singer, but had such little success that she disappeared from the music scene until 1975 when she recorded an album under the name of Visconti. Her real name is Carla Bissi but in Italy every knows her by her pseudonym, Alice. Her voice has a low timbre to it and from 1980 onwards she signed with EMI, like Battiato. Together they composed a song for the festival of San Remo, Per Elisa. They then went to Eurovision with the marvellous I treni di Tozeur and in 2016 they recorded a live album in Rome with a symphonic orchestra.

For those of us who knew him back then, he is forever linked to his albums in the early 1980s, Patriots and La voce del padrone [The master’s voice]. The second of these was the first Italian album to sell a million copies, including his popular Centro di gravità permanente [Centre of permanent gravity], where he says : “I can’t stand certain fashions/ Russian choirs/ fake rock music/ the Italian “new wave” [or the Spanish one, depending on the version]/ “free jazz”/ British punk /nor African gibberish”. It may be hard to believe but this song would take the dance floors of Europe by storm. His following album was called L’arca di Noè [Noah’s ark] and it contained the famous Volgio vederti danzare [I want to see you dance]. It is then that he started travelling to Turkey and learning Arabic. He had an interesting relationship with languages, recording versions of his songs in both English and Spanish and his complex discography contains up to 30 compilations in different languages.

Spiritual retreat

And then, just like that, Battiato disappeared. Some people suggested that he was suffering from depression but, in reality, he was saying his goodbyes to superstardom to seek refuge in the silence of meditation; saying goodbye to the lights, the attention and the fireworks, to remove himself from the world and try to resolve his internal problems. He grew a beard and cultivated a hermit look, retiring to convents for months on end to be alone with his thoughts. He appeared to have aged all of a sudden. He said to the now deceased Félix Romero in a Spanish TV show in 1997:

You see, it makes no sense to live without direction, without being able to answer the fundamental question: “Who am I?” You only have two options: ignore it, or do something about it. I have chosen the second path. I started to read to work of mystics, first Hindu mystics like (Paramahansa) Yogananda or Aurobindo, until I found a great man called Nisargadatta. Then I came to (Islamic) Sufism and to the Spanish mysticism of Saint Teresa of Avila and Saint John of the Cross. After all this, I feel that all religions have something to add.

Already in 1987, he had produced his first opera about Genesis, about how gods try to avoid a new flood by sending four archangels as messengers. The following year, he went to live with his mother in Sicily, publishing his album Fisiognomica with the marvellous song E ti vengo a cercare [And I come looking for you], which he sang for the Pope in the Paul VI Audience Hall in 1989. The experience brought him to tears but he said: “I am not a Catholic, even though I have very close friends in the Catholic Church, especially in certain convents, where I have always found the liturgy very moving”. He went on to explain: “I have my own spirituality. I am a religious man but I don’t have a church”.

Out of place

Always restless, in the 1990s Battiato entered a stage in which he mixed intimism and introspection with a mysticism free of religious proselytism. During this period he produced the album Come un cammello in una grondaia [Like a camel in a drainpipe], an expression that refers to something that is out of place. After the Gulf War, he said that he waited for “the best opportunity to buy a pair of wings and abandon the planet”. He recorded the album in London, in the Beatles’ Abbey Road studio with an orchestra. It includes impressive songs such as his litany to the Povera Patria [Poor Fatherland], saying that it is beyond saving (“non cambiera” …it won’t change), and that was before Berlusconi’s arrival on the scene! A similar diatribe led to accusations that he was an "anti-Italian traitor”. Some of his songs are prayers, such as L’ombra della luce [The shadow of light], which asks for protection against the shadows that are growing around him. It was his favourite song.

In the mid-1990s he began a collaboration with the philosopher Manlio Sgalambro, a pessimist thinker with metaphysical airs who had been writing since 1959, and had been translated to French and German. It was a non-academic kind of philosophy but its complexity distanced him from the general public, with convoluted and abstruse texts. To make it easier to swallow, to accompany him in his album L’imboscata [The ambush] (1996), he created a rock group with musicians like Billy Corgan, from the Smashing Pumpkins, and Peter Gabriel’s guitarist, David Rhodes. It is a cryptic album which begins with the reading of a Heracles text in Greek by Sgalambro, but it encloses a treasure, my favourite song by Battiato, La cura, a song that always gives me goosebumps.

Battiato mixed his idea of reincarnation with Islamic mystical Sufism or his own Catholicism, to which he became closer in the last years of his life. At the beginning of the century he surprised us again. The Fleurs albums contained covers of French and Italian classics of the 1960s, using a piano, a string quarter and a synthesizer. At the same time, he wrote music for ballet and experimental work, working with artists as varied as Jim Kerr, of Simple Minds, or the Argentinian Mecedes Sosa. He recorded live albums and made a film.

His later years

In his 2004 album, Dieci statagemmi, he sings: “I am not Muslim, Hindu, Christian nor Buddhist/I don’t opt for the hammer and sickle, let alone the tricolour flame (the symbol of the neoconservative Italian party Alleanza Nazionale, which in 1995 defended traditional Catholic values, law and order and the prohibition of narcotics, while supporting Israel and the United States)/ because I am a musician”. His declarations distanced him both from the United States and from the Taliban: “I try to be in the middle and stay away from fanaticism”.

He published his last album in 2013 (Apriti Sesamo – Open Sesame), but the tours continued until 2017. He lived with his brother Michele and his niece Grazia. He only listened to classical music and, despite having maintained the practice since the 1970s, had stopped meditating years earlier. At about the same time, he also distanced himself from Willigis Jäger, a Benedictine monk and zen master with whom he had been very close. He spent his last years in the company of the catholic priest Guidalberto Bormolini, who had been a missionary in India and who dedicated himself to “spiritual ecology, Christian vegetarianism, interreligious dialogue and preparation for death”. He officiated at Battiato’s funeral ceremony “following Catholic rites but without a mass”. Bormolini says that he and Battiato would pray together over the phone at night and that Battiato “was very prepared for this voyage”.

Reincarnation and the problem of pain

According to recent surveys, some 25% of the population in Western Europe and the United States says that they believe in reincarnation. There are many interpretations of reincarnation. Hinduism believes that every soul is individually reborn. Buddhism, however, does not believe in the independent existence of the soul. A distinction must also be made between the old belief in the pre-existence of the soul and the oriental belief in reincarnation. This confusion makes many believe that even primitive Christianity contained an idea of reincarnation.

Reincarnation seeks to provide an answer to the problem of the existence of evil, trying to assuage our age-old yearning for second opportunities and the amendment of past errors. The problem is that if an individual suffers today for an error committed in the past, according Karma’s law of cause and effect, the victim is guilty. It is therefore no coincidence that belief systems, like Hiduism, where this idea is most extended, are those where the problem of pain, which led to the birth of Buddhism, has historically raised more questions.

Can the problem of pain be explained by the cause and effect law of Karma? When Jesus is asked whether a man who was born blind had sinned or whether he was being punished for his parents’ sin, he gives a strange answer: “Neither this man nor his parents sinned….but this happened so that the works of God might be displayed in him” (John 9:1–3). Why do some people deserve more suffering than others? When a tower falls down and eighteen people die, Jesus says, “Do you think they were more guilty than all the others living in Jerusalem? I tell you, no! But unless you repent, you too will all perish” (Luke 13: 1–5). It is on the cross that the problem of evil is resolved since “God demonstrates his love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8).

New birth and resurrection

What we need, Jesus says, is a new birth. He talked of this to Nicodemus when he came to Him in the middle of the night (John 3). Through that experience of God’s Spirit we enter into a relationship with Christ, who frees us from the law of Karma. That is the great difference between the prodigal son stories told by Jesus and Buddha. While Buddhism teaches that we reap what we sow, Jesus’s good news is that there is a loving Father who forgives us and accepts us through his freely-given grace.

It is not about giving up our personality, living preoccupied with the eternal, but rather about a relationship and a communion with a personal God through the person of Christ. The eternal life announced by Christ is something that starts now; it is not just limited to survival after death. For the Christian, death is nothing but a passage to be with Christ (Philippians 1:23).

For that reason, Christians are not hoping for reincarnation but for resurrection. “Just as people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment, so Christ was sacrificed once to take away the sins of many; and he will appear a second time, not to bear sin, but to bring salvation to those who are waiting for him” (Hebrews 9:27–28). The believer is looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth inhabited by justice to live not reincarnated, but resurrected in the flesh (1 Corinthians 15). Because Jesus says: “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die” (John 11:25). That is the hope that I would have wished for Battiato, but we can still have it through faith in Jesus Christ.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The mysticism of Franco Battiato