The lady with the lamp

Florence Nightingale and the Fliedner family legacy.

20 MAY 2020 · 15:31 CET

Caring for the sick is one of many facets of pastoral care. If the coronavirus pandemic has shown us anything, it is the sacrifice of health workers whose bravery has amazed and reassured the rest of society.

While many of them have become sick and sadly even died, it has not prevented countless men and women around the world offering themselves as volunteers to replace them.

This year we celebrate 200 years since the birth of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), a pioneer figure in nursing. Her visionary determination championing hygiene and other sanitary improvements in medical care greatly impacted the politics of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her name is known around the world. Her connections with Spain are less well known.

Florence Nightingale was born in Florence, Italy (giving away the origin of her name), the younger of two children. Her family was wealthy and well-connected. Florence’s father, William Nightingale, was a rich landowner who gave his daughter a classical education, including the study of German, French and Italian. Her mother Frances, who herself came from a wealthy merchant family, boasted of her friendship with the well to do.

From an early age, Florence showed concern for the sick and the poor who lived in the village near her family’s estate in England. By the age of 16 she knew her vocation and, against her parents’ wishes, decided to devote herself to nursing, a profession considered menial and low.

At 17, Florence rejected a marriage proposal from a “suitable gentleman” and chose to follow her vocation, despite her parents’ protestations. In 1841 Florence visited the Lutheran Hospital of pastor Theodor Fliedner in Kaiserswerth, Germany. She spent some time there in 1850 as a student nurse.

Inspired by the diaconal leadership model of the early Christian church, Fliedner developed a plan so that young women could care for the needy sick. He therefore created the Kaiserswerther Diakonie in 1836, an institute where women could learn both theology and nursing. Florence was impressed by the rigour, the discipline and, above all, the Christian spirit and the high ethical and moral requirements of the centre, which became imprinted on her for the rest of her life.

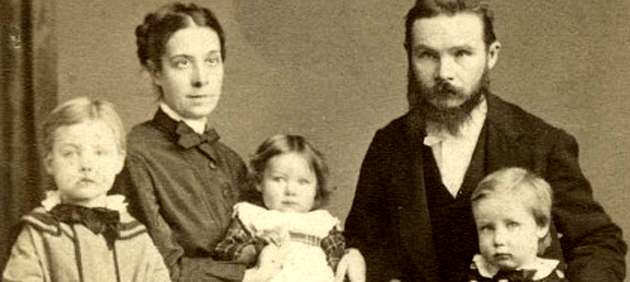

Theodor Fliedner’s educational legacy reached Spain once his son Fritz (known in Spain as “Federico”) established himself in Madrid in November 1870. Federico Fliedner (1845-1901) was a theologian, pastor, missionary, philanthropist, educator, teacher, journalist, editor, writer and evangelical poet. After he finished his theological studies (with a doctor’s degree from Tubinga in 1867), he worked as a rural teacher in Hilden.

Federico Fliedner arrived in Spain in March 1869, once freedom of worship was permitted. The following year he was ordained as a pastor and sent as “agent” of the German Committees of Help for the Gospel in Spain. He settled in Madrid on November 9th, 1870 and became chaplain of the German Empire’s delegation in Madrid. When he completed his baccalaureate, he studied medicine at the Central University. He attended the Church of Jesús in Calatrava Street in Madrid, where he collaborated in pastoral work.

In 1880 he acquired a dilapidated house, where King Felipe II had once resided, in El Escorial. He restored it and added a hospice for orphans, along with a school, the “House of Peace”. He travelled tirelessly, helping evangelical groups in the provinces and founded a school in each congregation to promote a higher level of culture and education in churches.

In 1873, Federico Fliedner founded the National and International Library, a publishing house with wide reach, boasting literary works, textbooks and journals. This eventually became the Calatrava Library. Two of the best known publications were “El Amigo de la Infancia” (“Childhood’s friend”), published between 1874 and 1939 and known to have influenced Miguel de Unamuno, and the “Revista Cristiana” (“Christian Magazine”) a scientific and religious newspaper. He also wrote, among others, biographies of David Livingstone and Martin Luther and adapted the lyrics (into Spanish) of about thirty -some well-known - hymns such as “Cabeza ensangrentada”, “Alma bendice al Señor”, “Noche de Paz” and “Oid un son en alta esfera”.

On his arrival in Madrid, Federico Fliedner received very clear instructions:

“Help the evangelical churches that had emerged during the second half of the 19th century in Spain to grow, providing a solid education and improving their organizational capacity by encouraging the collaboration of the evangelical people”.

As a result of this mission together with his Scottish wife, Juana (formerly Jane Brown), Federico Fliedner opened El Porvenir school in Madrid on 31st October 1897, Reformation Day.

To fulfil his vision, Federico Fliedner acquired some land in the Chamberí neighbourhood. No Spanish architect wanted to take on the project, but Joachim Kramer, a renowned Alsatian architect, agreed to build El Porvenir (1892-1897). Federico was also involved in the construction of other buildings, including those belonging to the Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Despite people’s misgivings and multiple problems completing the project, Federico was able to finish it with the political and personal help of the Prime Minister, Casanovas del Castillo and the Mayor of Madrid, Conde de Romanones.

The Fundación Fliedner in Madrid celebrates its 150th anniversary, coinciding with the 200th birthday of Theodor Fliedner’s most famous pupil Florence. A happy coincidence most worthy of celebration.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - The lady with the lamp